They are just seven names of thousands of black Americans murdered by lynching, many of which were included last week in a report from Bryan Stevenson's Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) that identifies victims of lynching between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950. It's a list that could go on for pages and, yet, still to this day remains incomplete.

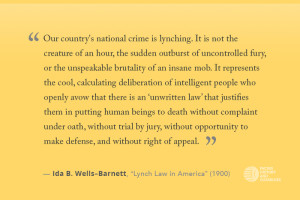

The history of lynching remains widely unknown today, especially among many white Americans. When the history is recounted, there is often a tendency to embed lynching in an overly-simplistic narrative. This includes the belief that lynchings took place in the dark of night, carried out by men covered in white sheets, a narrative that implies that lynchings were the work of extremists, and that they were distinctly Southern in nature—regional instead of national. Another assumption is that there must have been some crime that caused the lynching to take place. Something must have happened to provoke such violence. How is it imaginable that black Americans could have been murdered by their white co-citizens for asserting their humanity and hard won freedom?

The myths that surround lynching and its history can provide a source of comfort for those who articulate them, a way of explaining the seemingly inexplicable. It's a way of holding this history at a distance, of perhaps saying, That's your history, not mine, or that only unimaginable people (that is, people not "like me," not people that "I know") could have committed these crimes.

The reality of lynching in America, however, is quite different, something highlighted in EJI's groundbreaking report, "Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror." The report stands to bring Americans and the world another critical step closer to understanding the magnitude and impact of this recent chapter of United States history.

Many lynchings took place in the light of day, and often a town's most well-regarded white citizens were involved. Some people brought their children, dressed in their nicest clothes. And many made a day of it, inviting a photographer, then taking the photographs and using them as postcards to proudly share with friends and family.

This is a history of mass violence, of perpetrators who committed horrific acts, of active bystanders and collaborators, and of victims—human beings murdered because they were black Americans. Yet lynching remains at the margins of American history and United States collective memory.

Perhaps the EJI report presents an opportunity for educators to help change the conversation or, in many cases, begin one. The study documents 3,959 lynchings of black people, and finds at least 700 more lynchings than previously listed in any similar report. It painstakingly examines what EJI describes as "terror lynchings" in the 12 U.S. states where lynching was most active. Terror lynchings "were acts of terrorism because these murders were carried out with impunity, sometimes in broad daylight, often on the courthouse lawn."

Schools and classrooms are spaces where citizens are developed, where knowledge of one's local and national history and its legacies are critical foundations for developing an ethical, civic identity and becoming an informed civic actor. There are developmentally appropriate ways to teach about lynching, to engage with this history, and wrestle with its role in American life.

Questions that educators can ask include:

- What does it mean when the past is intentionally forgotten?

- How does a history move from one that is national to one that is regional, to one that ultimately becomes a burden of memory that rests solely on the victims and a few allies?

- How do we understand what triggers a choice to not remember?

- What are ways that violence or injustice have been remembered or commemorated for other histories?

To support educators in their efforts to teach this history, Facing History and Ourselves recommends the following resources and teaching strategies that can be used in several subject areas for middle- and high school students:

- Teaching Mockingbird is a guide to accompany Harper Lee's classic To Kill a Mockingbird. It explores themes of U.S. racial history and violence, justice and judgment, and moral development. Download now.

- "Emmett Till: A Series of Four Lessons" establishes important historical context to better understand the case of Emmett Till and its place within American history. Explore now.

- The short video "The Origins of Lynching Culture" provides an overview of the history of lynching and mob justice in the U.S. and explains how the perpetrators of lynching in the late 19th- and early 20th centuries used ideas about Southern womanhood and racial stereotypes to attempt to justify their actions. Watch now.

- At the end of February, we will publish The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy, a resource that explores the complex period of Reconstruction following the American Civil War and helps to frame the history of lynching in the U.S. and the rise of Jim Crow. Stay tuned.

- EJI's report explores transitional justice and the possibilities of truth and reconciliation, opportunities for communities—and the U.S.—to explore the past in all its detail and implications. The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission can make a powerful case study to explore how another nation attempted to address these issues. Learn more about the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission and view footage of the full commission.

Next month, Equal Justice Initiative Founder Bryan Stevenson will speak on issues of injustice and their legacy today at two free Facing History Community Conversations held in partnership with The Allstate Foundation, one in Chicago on March 18 and one in Cleveland on March 19. Learn more.