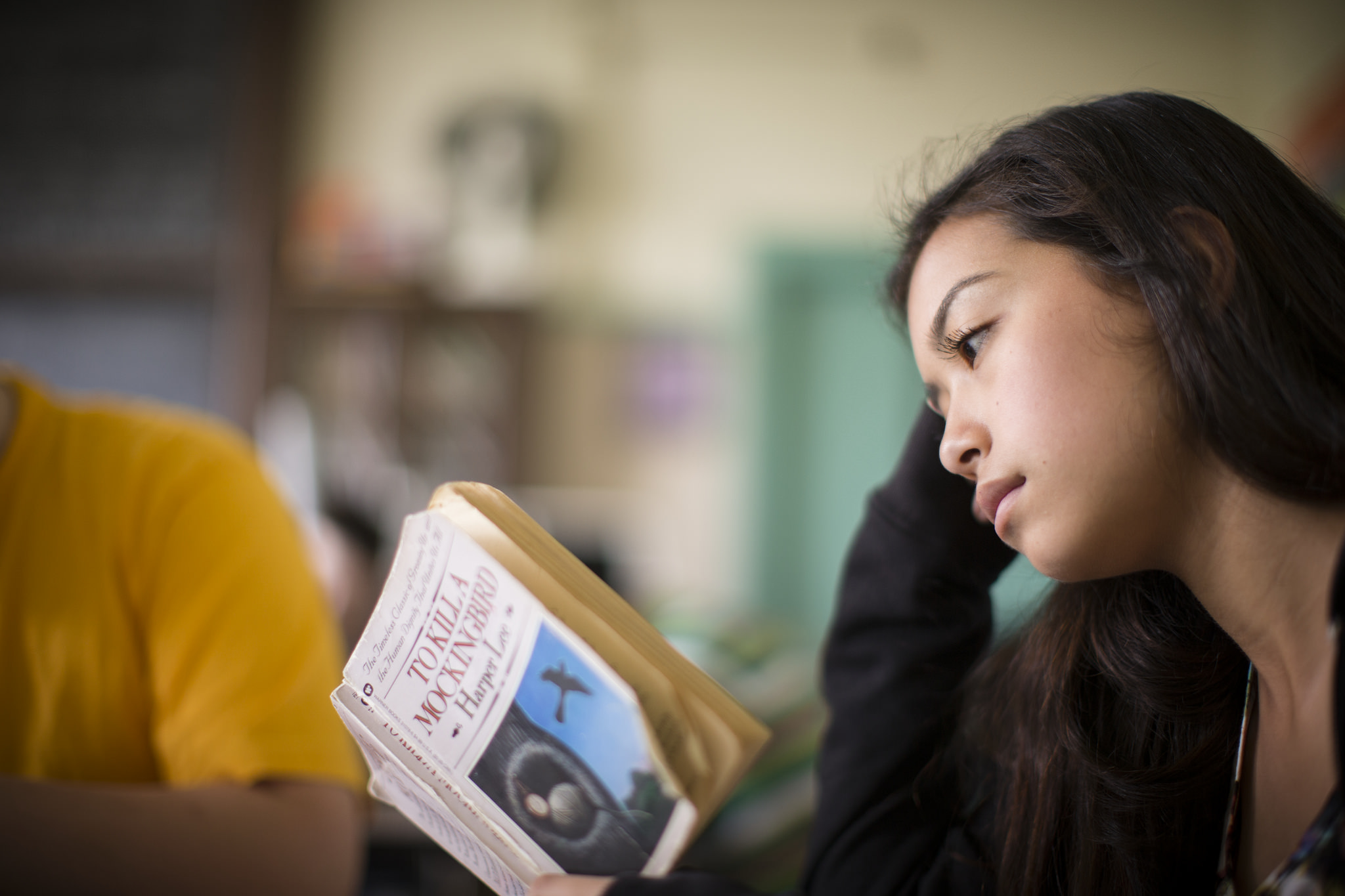

Nearly 54 years to the day after it was first published, the Pulitzer Prize-winning To Kill a Mockingbird comes out as an ebook for the first time on July 8.

The ereader version stands to make Harper Lee’s classic story about a young girl coming to grips with the spoken and unspoken rules about race, class, and gender in Depression-era rural Alabama accessible to a whole new generation of readers.

Its themes of moral and ethical development, the power of stereotyping and prejudice, the forces that shape the way people respond to difference, the role of upstanders in responding to injustice, crowds and power, the limits and possibilities of the law as a tool for social change, and the impact of the legacies of injustice on individuals, groups, communities and nations at large are just as relevant today as they were in 1960.

The release is a teaching opportunity, a chance to reflect with young people (and on our own) on the historical moment in which Lee wrote her book as well as on the themes To Kill a Mockingbird addresses. How can reading the book help us reach a deeper understanding of ourselves and our growth as moral and ethical people? How can it help shape the way we think and act? How can we cultivate in each other and ourselves the values, experiences, and skills we need to build a stronger democracy?

As is the case with any classic work of literature, To Kill a Mockingbird can prompt a variety of responses from readers, including both praise and criticism. While Lee’s novel is one of the most beloved books in American literature (it has sold more than 30 million copies worldwide), even those who love the book sometimes offer critical views of some aspects of the work. Any work of fiction that provides as complex and nuanced look at a society and its flaws as To Kill a Mockingbird provides of the Depression-era South is bound to be the subject of much debate.

Looking at responses to the book – both from history and today – can help students think about issues of memory and legacy, consider the historical moment of the 1960s, reflect on their own experiences reading the novel, and form their own assessments of it. Here’s one example, a review of the book from the July 3, 1960 Washington Post:

A hundred pounds of sermons on tolerance, or an equal measure of invective deploring the lack of it, will weigh far less in the scale of enlightenment than a mere 18 ounces of new fiction bearing the title To Kill A Mockingbird.

Harper Lee, the talented 34-year-old expatriate Southern who makes her literary debut with this engrossing novel, carefully eschews preaching, from either side of the Mason-Dixon line, about the grave issues which confront her native South. What she does, more adroitly than any recent novelist, is present in dramatic terms just how it feels to be a Southerner, with all that it entails of pride, pleasure, anxiety and shame...

The result is an unusually accurate rendering of attitudes that must be reckoned with in any solution to the South's contemporary problems. And yet, though so pertinent, the novel is not itself contemporary. There were no sit-in strikes during the depression years when Jean Louise (alias Scout) Finch and her brother, Jem, began to observe the human landscape of Maycomb County, Ala. No protests at all—but the seeds for them were being planted.

Her street is the world to Scout, a restless and ingratiating 6 at the outset. This world is bounded by grouchy Mrs. Dubose on the north, by the haunted Radley house on the south, and in winter, by the school yard just around the corner. Within these narrow limits occur the important small dramas of childhood, which as interpreted by Atticus Finch, the children's admirable father, become lessons in fair play, courage, and love.

"You never really understand a person until you climb into his skin and walk around in it," is his patient, oft-repeated advice, which really sums up the purpose and achievement of this novel. - Glendy Culligan, "Listen to that Mockingbird," The Washington Post, Times Herald (Washington), July 3, 1960. The full review is available in its entirety (for a fee) on WashingtonPost.com.

- Reading this assessment of To Kill a Mockingbird, what strikes a chord with you? What do you agree with? What do you disagree with?

- What else did you experience while reading To Kill a Mockingbird that this assessment leaves out?

- How do you explain the lasting popularity of To Kill a Mockingbird?

Comment with your answers below!

"Teaching Mockingbird," Facing History’s guide to Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird draws from history and the social sciences to help contextualize the book. It includes a series of mini documentaries, connection questions, readings of literature, and primary and secondary sources to deepen understanding of the historical period and human behaviors that would have helped shape the characters in the novel.