About two years ago, when I began reading draft chapters of Facing History’s new publication on the Reconstruction era in American history, I got to thinking back to how I learned about this period in high school in 1959 and in college, and also how I taught it to my students while teaching high school several years later in 1965.

In both my high school class as student, and later my high school classes as a teacher, I used the same textbook, David Saville Muzzey’s 1937 A History of Our Country, which for decades was the most widely used high school text on American history. Curious about what I learned and how I taught it, I dug out my well-worn copy and looked at how Muzzey wrote about Reconstruction.

According to Muzzey, the legislatures in the Southern states created after the Civil War, which included African Americans, were "sorry affairs" defined by corruption and supported only by "Northern bayonets." To preserve its way of life, "the South naturally resorted to intimidation," for example the Ku Klux Klan, whose "exaggerated violence" was reported in the Northern press.

That's how I learned about Reconstruction in high school, and undoubtedly how I taught it to my students. In between, in my college classes on American history, I was introduced to a newer, and now well-accepted, interpretation John Hope Franklin put forth in his 1961 book, Reconstruction after the Civil War.

Franklin challenged the claim that state reconstruction governments were ineffective, noting a number of significant accomplishments in extending political and civil liberties and creating education and economic opportunity within the states of the former Confederacy. Eric Foner, now the most notable historian on this period, notes these accomplishments as well.

Discussions about Franklin's book, however, led to a fundamental question about Reconstruction that underlies the Facing History resource:

Can state ways (law) make or change folk ways (longstanding beliefs and practices)?

Most of us in my college class thought the answer was no, that traditions of prejudice and racism were simply too strong and deeply seated to be challenged, let alone overcome, by state or federal legislation to ensure equal treatment of blacks in the South.

Perhaps we did not realize that we were voicing the very sentiments that politicians used for decades to justify government inaction and the insistence that any change away from segregation laws and policies could only come about through gradual activity, with great care not to upset entrenched attitudes and practices.

One of the components of studying and teaching history that has always fascinated me, particularly as I return to books that I read many years ago and to notebooks of course notes that I have never been able to bring myself to dispose of, is how interpretations of the past change, even over the course of a couple generations.

This is certainly true of Reconstruction. We now see how wrong earlier historians were to view that period as "the tragic era" even as we learn the reasons behind their position. But this might be said of other decades as well. To view the 1920s as simply a time of fun-filled "roaring excess" is to miss the remarkable and sustained economic growth and technological advances of those years, as well as the deep racial and religious prejudices behind immigration quotas, college admission policies, political campaigns, and court cases and decisions of that time.

To view the 1950s—the decade of my own adolescence—as simply a time of generational conformity and complacency is to miss the literary, artistic, and sociological expressions that questioned the dominant values of that period and both seeded and nourished societal movements that challenged foreign policy dogma and brought about significant accomplishments toward extending civil rights and equality of opportunity in succeeding decades.

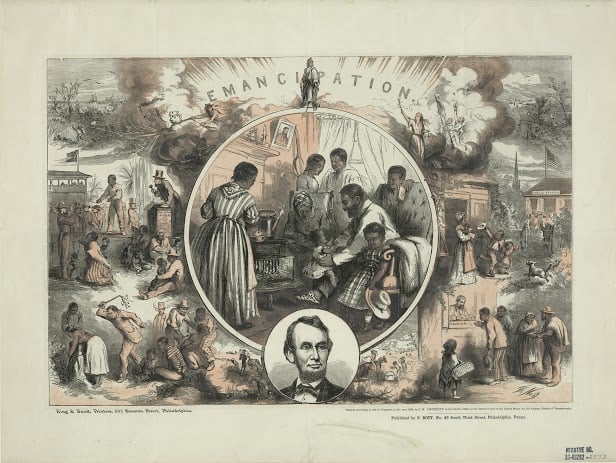

Thomas Nast's celebration of the emancipation of Southern slaves with the end of the Civil War. Wood engraving by Thomas Nast (1865), Library of Congress

Thomas Nast's celebration of the emancipation of Southern slaves with the end of the Civil War. Wood engraving by Thomas Nast (1865), Library of CongressHistorians know that interpreting what happened in the past is a process that continually undergoes change and revision. As teachers, while we want students to find meaningful connections between a time in history and their present worlds, we also need to complicate their thinking by helping them to understand that the legacies of that history are always vulnerable to the agendas and biases of the present—to the point where it can become a pernicious influence on law and policy and the choices that we as citizens of a democracy confront today and in the future.

Download Facing History's new guide The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy free now.

Register today for professional development that examines the dilemmas of healing, justice, freedom, and equality that Americans faced after the Civil War.

Download writing strategies that supplement Facing History's unit on the Reconstruction Era.