Facing History is excited to announce the two grand finalists for the 2017 Margot Stern Strom Innovation Grants! Out of 12 finalists, Catherine Epstein from Boston, Massachusetts and Jackson Westenskow from Aurora, Colorado were chosen to receive an additional $2,500 to work with Facing History on promoting their lessons to teachers everywhere. Their final lessons will debut this spring. In the meantime, read what Catherine has to say about how she uses letter writing to teach her students hard empathy. Make sure to read Jackson Westenskow's blog post about his project!

One afternoon in mid-September, a 7th grade student in my humanities class raised her hand.

“Can I ask who her parents voted for?”

I had just introduced a pen pal project between my Boston students and a classroom in Ozark, Arkansas. I hadn’t mentioned politics, the election, or national division. But this was—perhaps unsurprisingly—the first question from the class.

It also reflected the project’s reason for being. Throughout last year, I was struck at how often my 11- to 13-year-old students made sweeping generalizations about people who are politically different than themselves. Given the increasingly caustic national atmosphere that seemed to seep into my classroom, I wondered how politically opposed students could move beyond such reflexive rejection—and fundamental disinterest— in each other.

And of course, after the election, everyone seemed to be asking a similar question: How are we supposed to talk to each other right now?

But I didn’t know what it would mean for my students to engage with those they openly denounced and I didn’t know how to measure such an experience. I wasn't sure what would happen, which made the endeavor feel difficult and sometimes fundamentally dangerous.

But listening to an episode of the podcast On Being, “Pro-Life, Pro-Choice, Pro Dialogue,” shifted my approach to dialogue. It featured a conversation between Christian ethicist David Gushee and reproductive rights activist Frances Kissling. The tone was direct and sometimes tense, but it was also humane and curious. Gushee said that these discussions don’t always change his mind, but they remind him of Kissling’s humanity. “There is real value in the conversation,” he said. “It is transformative.”

Gushee and Kissling reoriented the essential point of engagement. The conversation might be challenging and uncertain, but it would have value if it worked to humanize students in each other’s eyes.

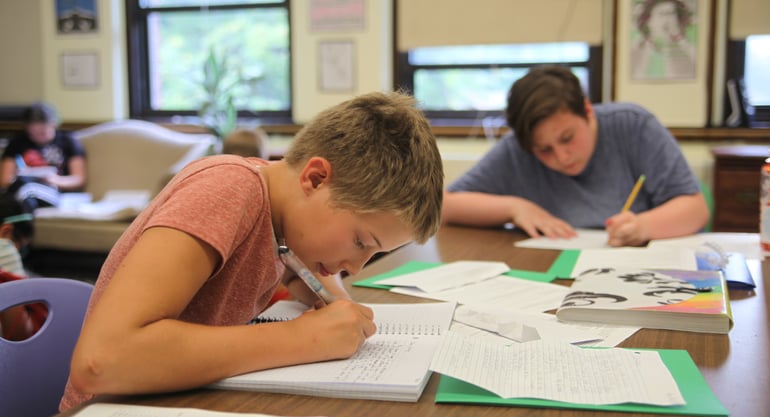

To produce this kind of dialogue with my students, letters felt especially useful. They slow students down from what they might otherwise email or text back, and they also create a material connection. They hold each other’s notebook paper and see each other’s handwriting.

When I began searching for a collaborator from a conservative region, Cherese Smith, a history teacher in what she described as a “rural, ultra-conservative public school” was one of the first to respond.

I was immediately struck by her enthusiasm for the project and she has profoundly influenced its implementation. With Facing History funding, I traveled to Ozark in early August, which gave us the chance to foster an authentic collaboration.

Cherese and I had ideas about how the project could work but were both inexperienced in this kind of dialogue, so we consulted with John Sarrouf at Essential Partners, an organization that specializes in fostering communication across difference.

John helped us see that in order for any productive conversation to happen, students must begin by seeing each other as people. Otherwise, communication often becomes heated, obstinate, and unproductive.

With this in mind, he encouraged us to include a question in their first letters: “What assumptions do you think others might make about you?” In her letter to me, Cherese wrote that others assume she is “dumb” because of her Southern accent and that “people think we are backwards and slow” because of their school’s “hillbilly” mascot.

In many of my students’ first letters to Ozark, they wrote, “I know this might sound stupid, but what’s a hillbilly?”

From there, we centered each letter around a theme to help the students explore a variety of subjects. They began by writing about family (“I’m ¼ Iraqi...my grandma is the only one people might discriminate against”), place (“I live in the city, so people don’t really own land. We measure in square feet, not acres”), and class (“Poor kids get treated wrong here, but kids with money get treated like they’re the queen or something”). Between now and the spring, they’ll discuss topics including patriotism, religion, gender, race, and gun rights.

In these first months, the project has felt energizing and fruitful for both classrooms. Cherese recently wrote in an email, “Corresponding with your students has been the highlight of our history class. As lifelong rural Arkansas residents, my students are being exposed to belief systems that they might otherwise never have known about or understood.”

And as the year continues, many of my original questions remain. I don’t know how my students will handle their most intractable differences and I don’t know how they’ll regard questions I’ve rarely had to face myself.

Both Cherese and I anticipate challenges. But we hope the students come away seeing the possibility of conversation—that they can, in fact, talk to each other right now.

Make sure to watch Catherine's original proposal video and read what Jackson Westenskow has to say about his project. We look forward to sharing their final lessons this spring!