I have been a teacher and assistant principal at Stuyvesant High School for 14 years.

Our school is located in lower Manhattan, just a few blocks north of the World Trade Center. We are one of New York City’s specialized high schools and draw students from all five boroughs. We have over 3,000 students in our 10-story building.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, my express bus dropped me at the Center's North Tower and I walked up a few blocks to school. I settled in for a busy day in the first week of classes.

At 8:40, the passing bell rang. I walked to the first classroom from my office shortly afterward, as I do each day to make sure all the teachers are in. Many of the students and the teacher were looking out the classroom window, which seemed strange to me.

Room 303 faces south, with a clear view of the North Tower. From where I stood I could see flames exploding from a giant gash in the side of the building. The classroom teacher and I looked at each other, both realizing something terrible had happened. I spent the next hour helping students call their parents. Initially, police told us to remain in the building. But when the second plane hit, we got the order to evacuate.

I still teach in room 303 today, and as each anniversary of 9/11 approaches, I struggle with meaningful ways to cover the attack, the events surrounding it, and the importance of this historical moment for our lives today.

Teaching about 9/11 on 9/11 is a challenge for most teachers. For those of us who start classes after Labor Day, the anniversary occurs during the first full week of classes. We hardly know our students. We don't know if any of them were personally impacted by 9/11. Many of us can become overcome with emotion while teaching about it as well. Since students at Stuyvesant walk past or close to Ground Zero as they travel to and from school, I wonder if teaching about 9/11 will cause anxiety for some of the children. Yet, it is incumbent upon us as educators to teach about 9/11, even if the memories are still painful. As teachers, it is always our hope that in studying how history unfolds and understanding why nations or people act as they do, we will be better equipped to build a better future.

Teaching about 9/11 on 9/11 is a challenge for most teachers. For those of us who start classes after Labor Day, the anniversary occurs during the first full week of classes. We hardly know our students. We don't know if any of them were personally impacted by 9/11. Many of us can become overcome with emotion while teaching about it as well. Since students at Stuyvesant walk past or close to Ground Zero as they travel to and from school, I wonder if teaching about 9/11 will cause anxiety for some of the children. Yet, it is incumbent upon us as educators to teach about 9/11, even if the memories are still painful. As teachers, it is always our hope that in studying how history unfolds and understanding why nations or people act as they do, we will be better equipped to build a better future.

I have developed a lesson that can last one to three days for high school and upper-level middle schools students that focuses on remembering and honoring the events and the victims of 9/11. I have taught this lesson the past several years and hope it can be helpful for educators and community – in New York and around the world – as you plan to commemorate this event, its victims, and its upstanders.

Preparation:

I recommend giving an oral history homework assignment as soon as possible after the start of term in which they meet and talk to individuals (family, neighbors, friends) about what those people experienced on 9/11. I find that having students interact with others this way helps students connect to the events in a more personal way and allows them to hear and experience multiple perspectives. The 9/11 Tribute Center has resources on conducting oral histories that are very helpful in crafting the assignment. I have used several of their recommended questions to assist the students in creating respectful yet pointed questions for their interviews.

Beginning the Lesson:

I ask students to bring their oral history reports to class on September 11 and we share them in small groups, which I find helps to build a level of comfort amongst the group. I then ask for volunteers to share their stories aloud. Depending on the group, and whether or not you are planning on a multi-day lesson, this could take anywhere from 10 to 20 minutes.

I then introduce the 9/11 National Memorial Interactive Timeline to give students a sense of how the day unfolded on that morning. I focus on American Airlines Flight 11, which was the first plane to hit the North Tower of the World Trade Center. I play an audio recording of flight attendant Betty Ong, the lead stewardess on Flight 11, who phoned authorities from the air to report the hijacking as a way to share with students the impact one individual can have when they stand up and act in the face of difficulty or fear. The information Ong conveyed was instrumental in later identifying the hijackers and understanding how they carried out the attack. After we listen together, I ask students to do a free write reflection and then ask for volunteers to share their thoughts. This gives the students time to really think about the recording. I find students are amazed at Ms. Ong's clarity and resourcefulness in the crisis and listening in this way helps them to understand the power that one individual can have for good in the face of evil. I never want my students to lose this sense that individuals and groups of people can be forces of good.

Using Literature to Make Connections: The Stories We Tell:

Next I bring events of that day back to Stuyvesant High School by using selections from with their eyes: September 11th: The view from a High School at Ground Zero, edited by Stuyvesant English and drama teacher Annie Thoms. In the weeks following the attack, Thoms, inspired by the work of writer and actor Anna Deavere Smith who often explores difficult moments in history and current events through interviews of people who lived through them, asked students in her class to speak with members of the school community about their experiences on 9/11. Uncovering different perspectives, the students turned these interviews into monologues, which they performed for the school that February. The book collects these monologues and while any of them work well for this lesson, I use Ilya Feldsherov’s “Piece of my Home.” Ilya was a senior at Stuyvesant in the fall of 2001 and September 11 was his senior picture day. His piece has both elements of humor and gravitas, which the students respond well to and to which they can relate. I like to have a student read the piece aloud for the class and have developed a few questions that can be discussed afterward in small groups or with the class as a whole:

- Why does Ilya describe what he was wearing in such detail? Why is this important for him?

- How does Ilya describe the routines of a regular school day and how those events are intermingled with the extraordinary events unfolding before him on that morning?

- What do you think of Ilya’s father’s reactions?

Memory and Memorials:

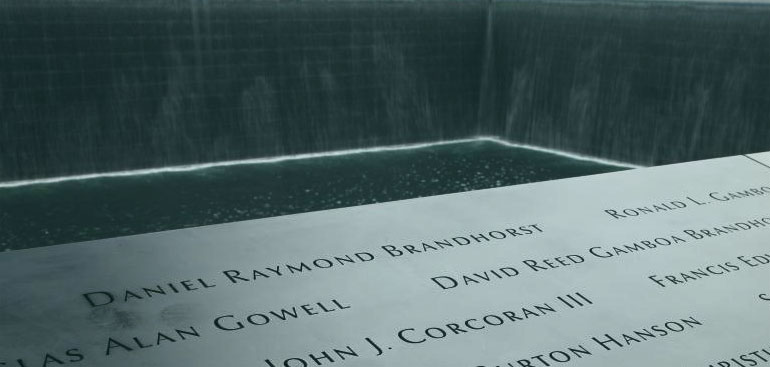

At this point in the lesson, I ask students to think about how we commemorate the lives of our loved ones who have passed away. I ask students to share in small groups any family traditions they participate in or have witnessed. After some discussion, I introduce the poem ‘The Names,” which former United States poet laureate Billy Collins composed to mark the first anniversary of 9/11. I ask students to first read the poem silently. I then show a clip of Collins reading the poem aloud on PBS. As he reads names of the victims, their images are projected onscreen. It is very moving. I have a series of questions that can be asked, depending on how much time you wish to spend on an analysis of the poem:

- Was there an image in the poem that struck you or that you found moving/interesting?

- How does Collins use both urban and bucolic imagery in this poem? Why do you think he does this?

- How does Collins juxtapose the childlike innocence and the horrific in this poem?

- Collins’ imagery goes back and forth between the grand (“pale sky” or “over the earth and out to sea”) to the minute (“yellow petal” or “tip of the tongue”). Why do you think he does this?

I like to compare Collins’ piece to Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Facing It,” which relates to the Vietnam Memorial. Komunyakaa is an African American Vietnam War veteran and Nobel Prize-winning poet. “Facing It” is a beautiful piece that challenges students to think about how we honor the dead. I recommend projecting an image of the Washington, D.C. Vietnam War Memorial while reading the poem.

Choosing to Participate:

A final part of the lesson involves community building. I again use resources from the Tribute Center for this element. In particular, I like to play the testimony of Principal Ada Dolch. Principal Dolch’s school was located across the street from the towers. She safely evacuated all her students all the while knowing her own sister was on one of the top floors of the towers. Her sister perished. Yet, Ms. Dolch found a way to create something positive from the experience. You can play her interview online. Using Ms. Dolch as an example helps students remember that they can make a difference. In the face of adversity, throughout history, individuals and communities have worked together to improve the lives of others. September 11 was no exception. And ending the lesson by showing the ways in which the actions of others can make a long-term impact empowers students to help make the world a better place.