The killing of Cecil the Lion on July 1st attracted both heavy news coverage and a flurry of responses on social media. An interesting thread emerged from these responses: questions about how people can become so outraged over the death of a lion on the other side of the world, when there are larger scale, or more local, stories of individuals and groups of people suffering unspeakable violence and injustice. The underlying theme that unites many of these confrontations is “Which story about tragedy or injustice is more worthy of our attention?”

From a Facing History perspective, we would reframe this question. Rather than asking which story is more worthy of our attention, we encourage students to think about how we respond to injustices, small and large, local and global. We live in a world where news cycles offer no shortage of distressing stories to consider, and this relentless newsfeed impacts how we respond to the information we receive. In her book High Tide in Tucson, novelist Barbara Kingsolver describes how people numb themselves to disturbing information:

“Confronted with knowledge of dozens of apparently random disasters each day, what can a human heart do but slam its doors? No mortal can grieve that much. We didn’t evolve to cope with tragedy on a global scale. Our defense is to pretend there’s no thread of event that connects us, and that those lives are somehow not precious and real like our own. It’s a practical strategy, to some ends, but the loss of empathy is also the loss of humanity, and that’s no small tradeoff.”

After describing a psychological study indicating that the suffering of one child (Rokia, a fictitious 7-year-old in Mali) invoked more compassion than the suffering of 21 million starving Africans, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof posits that “what we need isn’t better laws but more troubled consciences—pricked, perhaps, by a Darfur puppy with big eyes and floppy ears.”

This lens can help us and our students grapple with people's inclination to empathize with and become outraged by individual narratives like Cecil the Lion, yet be unresponsive, or more passive, when faced with larger tragic or violent events.

In the documentary film Reporter, comedian Stephen Colbert facetiously asks Kristof, “Why should we pay attention to the rest of the world?” The responses to the Cecil the Lion coverage raise the inverse of this question: “Why aren’t we paying attention to what’s happening right here at home?” These are both important questions to ask our students as we encourage them to consider their role in the broader world. While there is no right answer, this conversation is important, both to engage students intellectually, emotionally, and ethically, and to foster in them a sense of agency to promote their civic engagement.

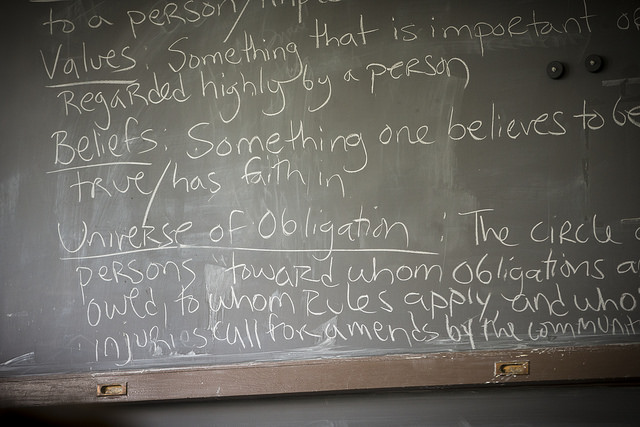

The Universe of Obligation is a concept teachers can use to help students reflect on their relationship with the world around them. Sociologist Helen Fein defines this idea as a circle of individuals and groups “toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for [amends].” As a starting place, teachers can help students consider who is a part of their own Universe of Obligation, using a graphic organizer of concentric circles. It becomes a tool to think about how individuals and groups, in history and in literature, include or exclude others from their respective Universes of Obligation.

A next step can be to engage students in thinking about how to expand their Universe of Obligation, pointing out that broadening their empathic sense of responsibility does not necessarily mean they need to exclude those already included. Caring about the senseless killing of an endangered animal does not mean that one cannot also care about the injustices happening to people in other parts of the world and in their own communities.

We want our students to be engaged citizens. We have a responsibility to give them structures and models to confront the volume, and content, of information they receive, and encourage them to ask probing, critical questions. Civilized society, and democracy in particular, must be worked at if it is to be preserved, and in order to do this we must understand our relationship to events unfolding around us and our related roles and responsibilities. By asking our students to engage with the world around them, locally and globally, we help them begin to understand, and ultimately to take on this responsibility.

Adapted from Facing History and Ourselves resources, including the Choosing to Participate guide and Teaching Reporter: A Study Guide to Accompany the Film Reporter.