A book recently came into my possession that has been tossed around in my family like a hot potato for several generations.

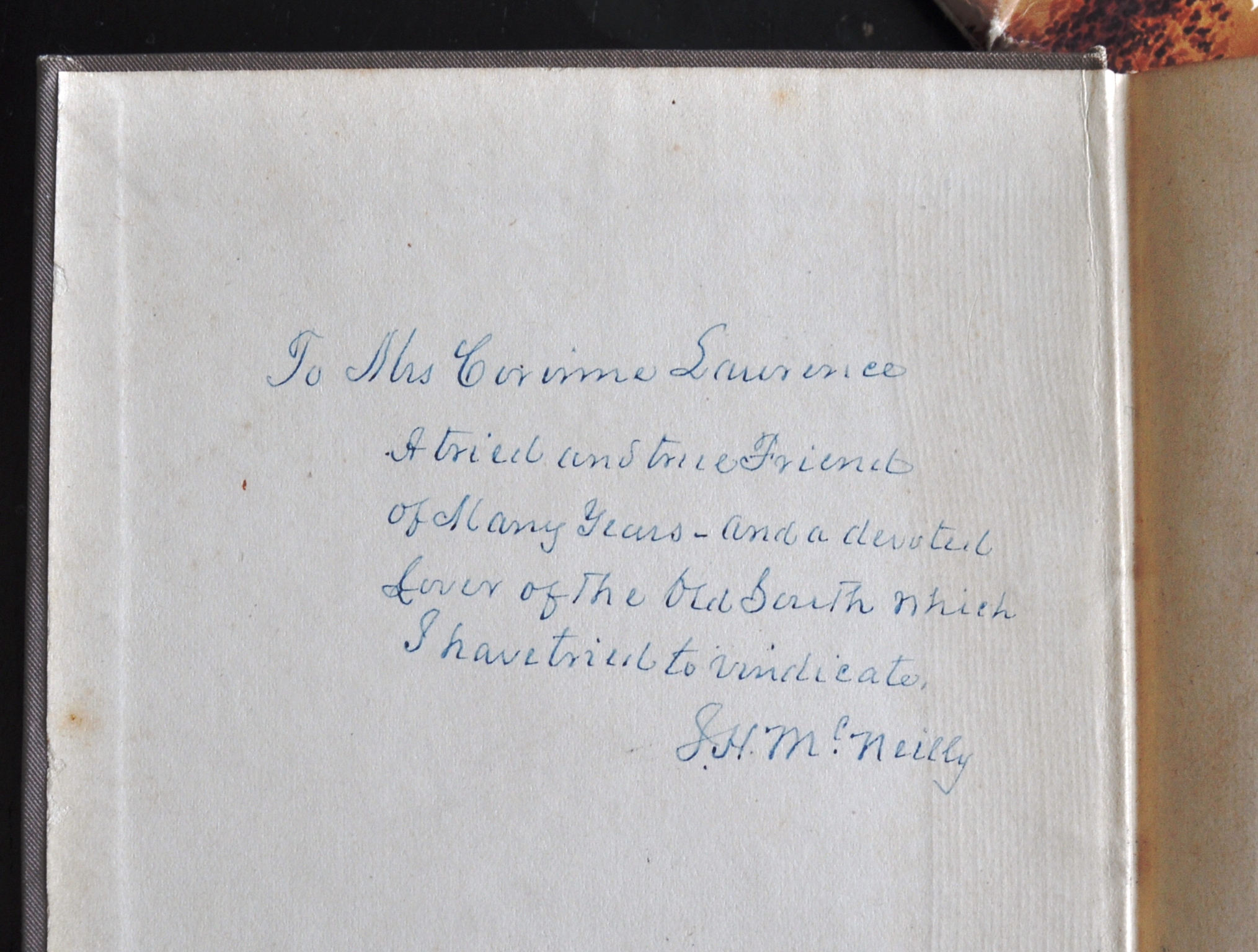

Entitled Religion and Slavery: A Vindication of Southern Churches, the book's author was James McNeilly, a Presbyterian minister and confederate veteran from Nashville, Tennessee. Inside the front cover is an inscription from the author to my great-great-great-grandmother.

"To Corinne Lawrence: A tried and true friend of many years—and a devoted lover of the Old South which I have tried to vindicate."

Last June I moved back to my hometown of Memphis after living in Los Angeles for 23 years. In the fall, my Aunt Caroline came to visit and brought the book. No one in the family wanted anything to do with it, but, at the same time, they felt that it was somehow too important to throw away. Published in 1911, the book defends slavery as benevolent and appropriate for an "inferior race."

McNeilly wrote that he endeavored to prove that, in the old system, slaveholders did discharge their "religious responsibilities for the souls of their slaves." He goes on to explain that the evils of slavery the abolitionists fought were "misrepresentations and misunderstandings" told by people with prejudice against southerners.

Passages like this one had been underlined:

"We are to remember that the negro in this land is at most only three hundred years from the most degrading savagery and the most oppressive slavery to the barbarous chiefs of his own race. It will require long training, in addition to that he received in Southern slavery, to eradicate some of those baser instincts which came to him from generations of savage ancestors."

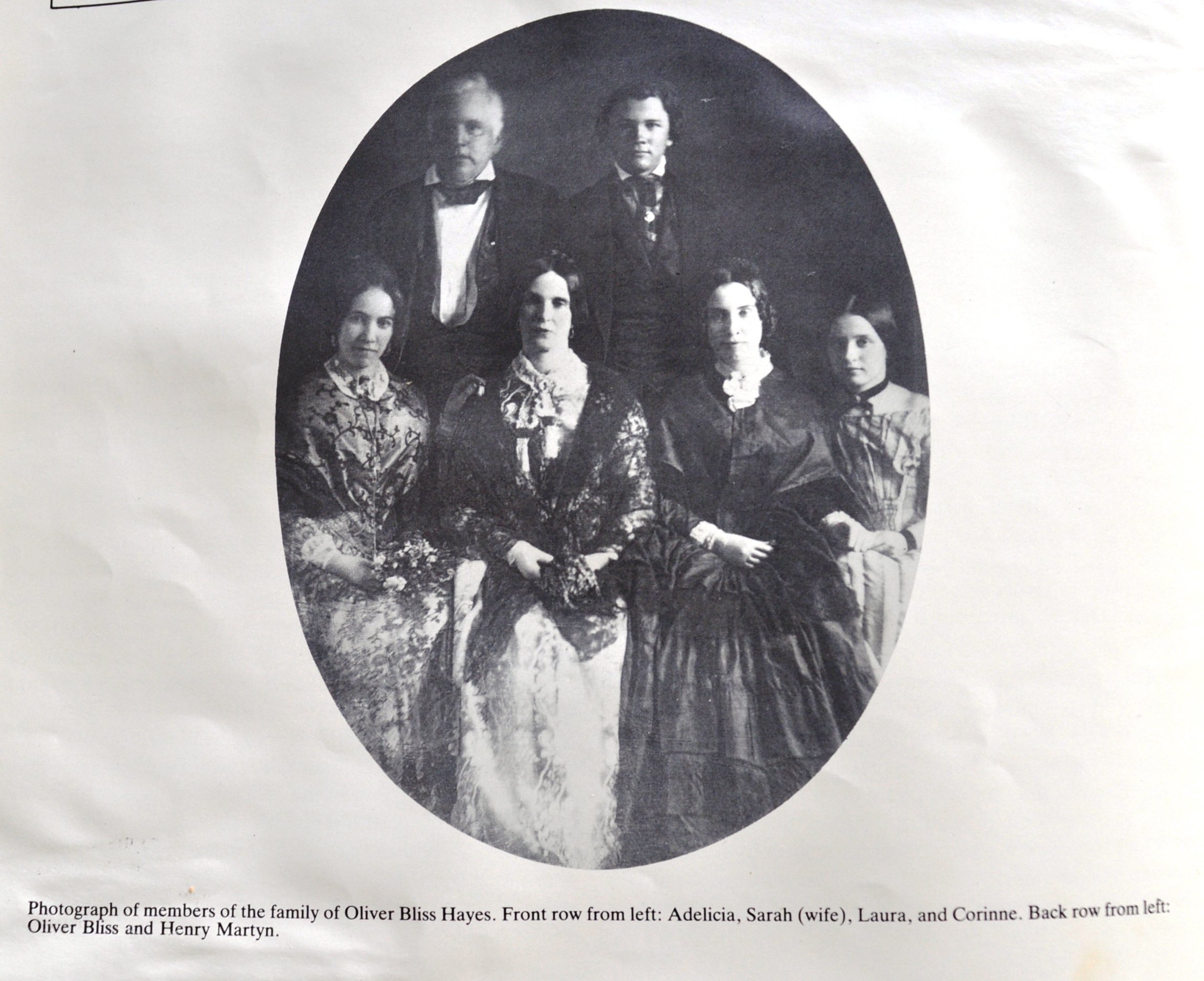

When I opened it and saw the inscription, the stories I heard growing up about my great-great-great-grandmother Corinne came flooding back. She was from a prominent Nashville family and her sister, Adelicia Acklen, was the owner of the Belmont Plantation in Nashville (now the site of Belmont College) and famous in her day. My grandparents were always very proud of this heritage and the class status it conferred. They wanted to pass that along to me, telling me we were from a "good family." They could point out pieces of furniture from Corinne's antebellum home which would "one day be mine."

A photo of the author's ancestors. Adelicia is pictured on the far left while Corinne is on the far right.

A photo of the author's ancestors. Adelicia is pictured on the far left while Corinne is on the far right.As an adult, I began to do my own reading about our family. One day I came across a fact that had never been mentioned at the dinner table. At the time of the Civil War, great-great-great-aunt Adelicia owned over 700 slaves. Her first husband, Isaac Franklin, was a very "successful" slave trader. Their plantation in Louisiana, Angola, is now the site of the state penitentiary. That irony is not lost on me.

Growing up, we did talk about what happened to the generations of our family after the Civil War, but not once did anyone ever ponder what happened to the former slaves. How could a family have so many stories and memories to share over so many generations and yet have this silence about certain realities from the years after the war?

Leafing through the pages of Religion and Slavery provided a glimpse into the period of reconstruction after the Civil War and was a reminder of the enormous change that took place in the American south, as well as the resistance to that change—the myths, misinformation, and misremembering that was passed down through generations.

I ask myself all the time, What do I do with this past?

I don't feel guilty about my ancestors. I am not responsible for their beliefs and actions. I do find it difficult to grapple with the enormity of the inhumanity that transpired, and how we have still failed to address it. What I find most chilling is how far the legacy of those prejudices can reach into the future. It has given me a firsthand understanding of how this kind of hate gets passed down.

As a child I had no reason to question what the adults told me: that our family was great, that the South had lost the war, that somehow our society came back together again. What would have happened if I hadn’t learned critical thinking and questioning, been exposed to other experiences, or been taught to walk in someone else's shoes? What would my beliefs be now? Who would I be? And how hard would it be, today as an adult, for someone to challenge those deeply-held, yet deeply wrong, and injust beliefs?

A few weeks ago, our Memphis office hosted a two-day workshop on our new resource, The Reconstruction Era: The Fragility of Democracy, a teaching unit that explores this pivotal period in American history and the challenge of promoting both healing and justice after the Civil War. In the seminar, participants learned that the history most of us were taught was only part of the story. They also learned about ways African Americans were active participants in the pursuit of citizenship and freedom. One teacher reflected about the importance of teaching this history:

"You get to right a wrong. As teachers, we have the ability to teach it right. It gives us hope—that the positive examples say to our students—one day things might be different."

It's a hope I have, too. Exploring this history, and my ancestor's perspective, illuminates how the past shapes the present—both on the societal level and, in very personal ways, for individuals. I am grateful that I have had other perspectives, including from my family, so that I was able to interrupt the misremembering of this past and begin to seek the truth. While I am not responsible for what my ancestors did in the past, I am responsible to help the next generation uncover the truth about this history.

Download a free copy of Facing History's new resource The Reconstruction Era: The Fragility of Democracy today.

If you decided to explore your family and its history, what places would you visit? Whom would you interview? What questions would you ask? Comment below!