A woman who was interned in Auschwitz came to speak to our class.

We were in 7th grade and she gathered us around her. Stretching out a wrinkled wrist, she displayed the numbers staining her arm like knotted veins. We spent a semester with lessons adapted from Facing History’s resources on the Holocaust and human behavior, attempting to imagine her past. We read Eli Wiesel’s Night, watched Schindler’s List, and studied 60-year-old Nazi propaganda posters. I wrote and performed a monologue from the perspective of a Danish resistant fighter, imagining a night in 1943 when Danes smuggled to Sweden many of the country’s 8,000 Jews.

While my family had not lost relatives in the Shoah that we know of, the Holocaust was part of our heritage. Every year our temple lit yellow candles: “Never Forget.”

Over a dozen years later, I found myself last winter constructing a curriculum about another genocide, this one not quite so far removed in time or place. I was living in the sweltering slums of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, teaching at a dormitory and leadership center for bright, young college women.

These women had come from all across the kingdom of Cambodia – from Battambang province on the Northern Thai border, from Svey Rieng protruding out into Vietnam, and from the province of Siem Reap, home to the jungle temples of Angkor. They came to the capital to become lawyers, engineers, doctors, midwives, and business women. Their parents were farmers and fishers, men and women who suffered interrupted educations as children living through the Khmer Rouge genocide of the 20th century.

As I grew to know my students, I realized that they knew very little about the genocide that had consumed over two million Khmer. They knew even less about other genocides across the globe. Cambodian schools cover the killings with a cursory sweep. And while all of my students have family stories – of starvation or slaughter – the years under Pol Pot are rarely discussed.

In Cambodia, granular photographs and written testimonials are not needed to imagine the past (although both exist in abundance). The stains of genocide stubbornly cling to the landscape. Sometimes literally, as I found at Tuol Sleng, a Khmer Rouge torture prison converted from a school, where the tiled classroom floors are still glazed in splashes of blood.

The stains are visible in the once-more clogged streets of Phnom Penh, filled not just with restaurants and tourists, universities and half-constructed office buildings, but with limbless beggars, the breathing evidence of a countryside seeded with landmines.

Stains emerge from the ground in the surrounding countryside. In the crater-filled orchard of the Choeung Ek killing fields where the soil still blooms with femurs, molars, shards of skulls, checkered scarves, and babies’ jumpers.

And there are stains to be found in the shadowed chambers of the genocide tribunals, still ongoing, where in the 35 years since the fall of the Khmer Rouge, only a single perpetrator has been tried, convicted, and sentenced to prison.

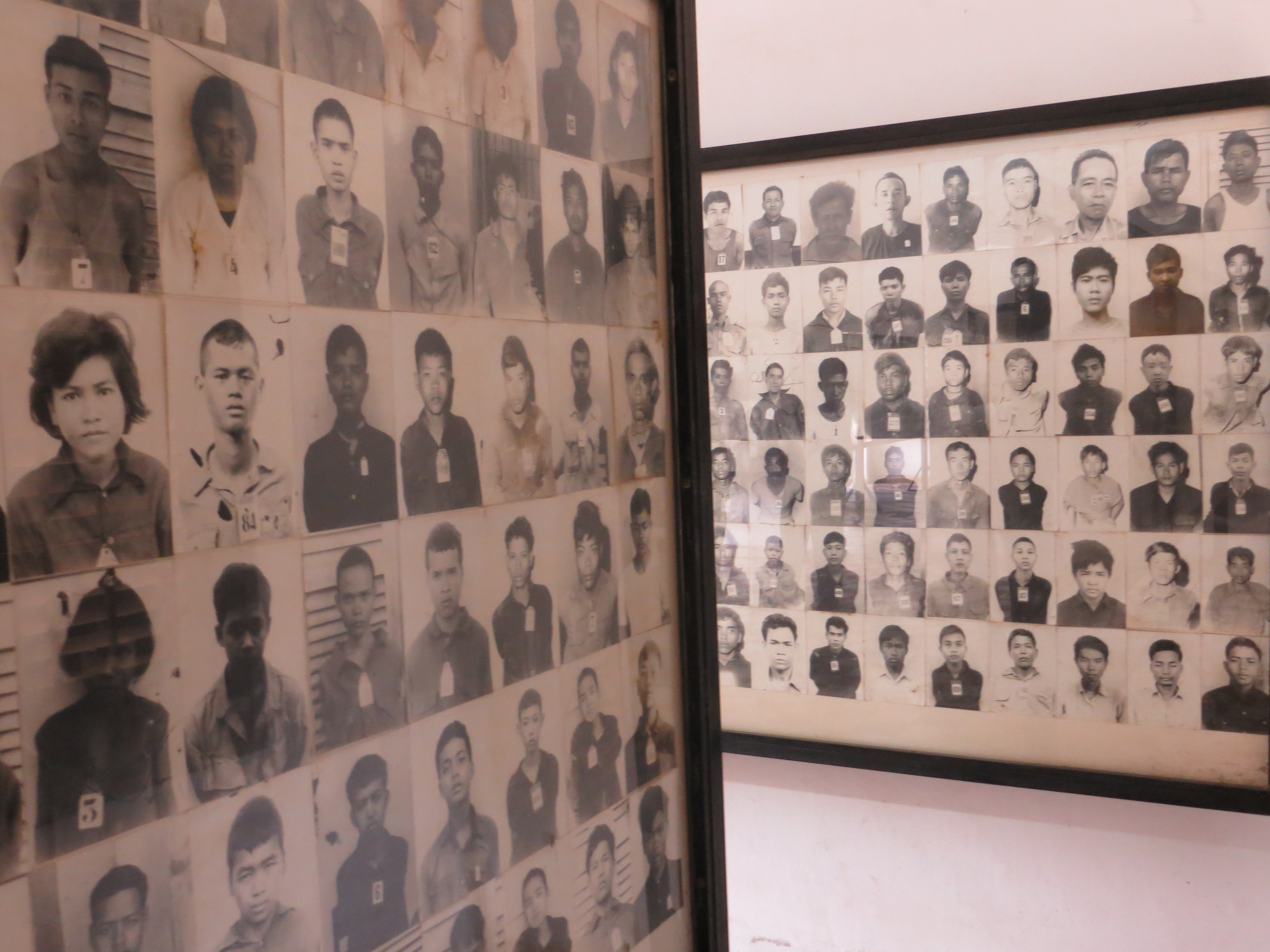

A catalog of those convicted of treason and killed at Tuol Sleng Prison, Phnom Penh (Jessica Lander)

A catalog of those convicted of treason and killed at Tuol Sleng Prison, Phnom Penh (Jessica Lander)Teaching the Cambodian genocide in Cambodia to Cambodians is not about reanimating the past. Here, the past is still present. Slogans like “Never Forget” are superfluous in a country where so many suffer from untreated Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). When does a country’s recovery require a singular focus on the future, and at what distance can one begin to re-examine the past?

My students are just the first generation post-genocide. My hope in writing a curriculum about the Khmer Rouge was to create a space for understanding, for asking questions, and perhaps for healing.

I began to shape an intensive course on comparative genocide. We would start many miles away and many years ago. We would begin in Germany, with other killers and other victims. We would talk of the mechanics of genocide from the sheltering distance of time. Then we would move forward, provide context, show students what happened elsewhere in the world. We would speak of Rwanda and Bosnia. Only then would we turn to Cambodia.

Rather than read about the past, as we did in our 7th grade Facing History classes, we would speak of their past. I built time into the curriculum to share stories that were not spoken of in my students’ homes. We would walk the 15 blocks to Tuol Sleng prison and, schedule permitting, spend a day at the war tribunals on the outskirts of the city.

At some point, 30 years from now – or maybe 50 – there will be only stories and recorded memories. Bones and clothes will cease to sprout from the ground. Perhaps then, when the horrors of history are no longer so abrasively palpable, the genocide will be taught in classrooms across the country, students learning to “Never Forget” just as I did.