As a 12-year-old African American boy fresh off the influence of Malcolm X’s autobiography, I didn't always appreciate the ethical stock of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I remember watching a news report about his birthday and remarking, to the dismay of my mother that, "Martin Luther King was a sell-out."

Dr. King's approach of destroying hate and not its host was lost on me for decades. It had been drowned out by an American social dynamic where I was constantly bombarded with notions of unbridled criticism and blatant disregard for empathy as the pinnacle of social justice and activism. It wasn't until I had been confronted with being stigmatized as a Muslim that I began to reconsider my intellectual position along with Dr. King’s methods and how the civic strategies he used over 50 years ago were so complex and nuanced that we're still unpacking many of them today.

If each of us took a moment to reflect on the complexity of our identities, I think we'd find at least one part of it has been the target of ridicule, hatred, and/or prejudice at some point in history. Dr. King took the nonviolent methods that Mahatma Gandhi established and transformed them even further. He didn't shy away from sharp but constructive critique of public policy but, he also proved that you could affirm a role in the secular world and still be a proponent for social justice. Some would argue this is more difficult than separating yourself from mainstream norms as Gandhi had done.

Dr. King wrote in his famous Letter From a Birmingham Jail in 1963, "We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied to a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly." Dr. King was cognizant of the interrelatedness of different communities and the complicated identities that define them. No one in America has just one identity. We either have multiple layers at one time, or we have a past. Each of us chooses which slither of our personalities should be most prominent at a given time depending on where we find ourselves in life and what exposure will be most advantageous. In today's charged climate of pointed and divisive speech coming from all sides, it's important that we remember his words, "Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds."

One of the goals of Facing History is to foster a better understanding of opposing views by facilitating and sometimes even advocating challenging conversations between educators in our workshops. Dr. King was a revolutionary in this regard because while some of his peers criticized his call to direct action in the form of sit-ins and protests, he insisted, "There is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth." Thanks largely in part to his benevolent writings and speeches, I've come to realize that seeking justice is a joint venture. Each side has a portion of the truth and to listen to an opposing opinion is not diminishing but rather emboldens justice and allows it to live and breathe. His goal wasn't necessarily to prove the other side wrong, but to get them to understand a perspective they perhaps hadn't previously considered.

At Facing History, we use resources like, “Fostering Civil Discourse: A Guide to Classroom Conversations” and teaching strategies like SPAR to give students the space to be reflective and map out moral and ethical choices through the lens of history. By using historical case studies without making analogies to current conditions, we provide a vehicle for students to develop their own lens. We give them agency to decide which issues are most worthy of debate and which are not. One of the greatest legacies of Dr. King was that he was keen to use strategies that as he said, "...do not create tension, but merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive."

In the spirit of those civil rights giants who sacrificed so much, we should shape our students' classroom experience to be a training in preparation for various iterations of civic participation. While we've learned a plethora of lessons from the life and civic struggle of Dr. King, the one that sticks out most for me is that social justice is achieved not necessarily in a glorious outcome, but in all the little tasks leading up to it. So that what is needed is not one charismatic figure who appears from behind a curtain to address the adoring crowd, but many average civically-committed individuals who show up every day to perform the mundane tasks that ensure a brighter future for our children.

Need materials in time for honoring Martin Luther King, Jr. Day? Check out lessons like, “The Philosophy of Nonviolence” and “Taking a Stand: Models of Civic Participation” to bring Dr. King’s legacy of civic participation into your classroom. You’ll find these lessons and others in our unit, “Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Movement 1954-1985.”

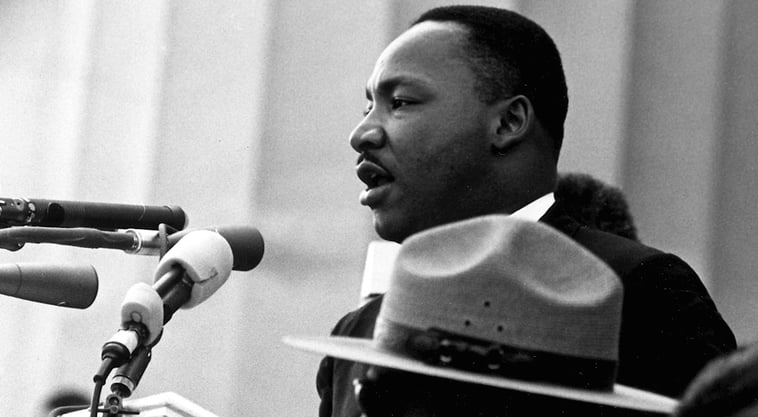

Photo Caption and Credit: Dr. Martin Luther King giving his "I Have a Dream" speech during the March on Washington in Washington, D.C., on 28 August 1963. Photo provided by Wikimedia Commons.