Facing history is difficult. Facing ourselves may be more so.

Shot by Shot: The Holocaust in German-Occupied Soviet Territory, a new eBook from Facing History published this month, asks us to do both.

In the years before the Holocaust, a young Polish Jew named Raphael Lemkin tried to warn diplomats that in the aftermath of the mass murder of the Ottoman Armenians by their own government, they needed to do something to stop similar slaughter in the future. It had happened before, he said, and it would happen again.

Lemkin’s ideas were dismissed.

That was Turkey. Things like that happen too rarely to legislate.

As the Nazis rose to power, Lemkin, by this time an international jurist, drafted new laws to prevent what he would later define as genocide. Less publicly, he also warned his family to escape Poland.

There is a history of the Holocaust with which many of us are familiar. It is a story that begins with racial and religious discrimination against the Jews of Germany, escalates with the isolation and ghettoization of Jews in Poland, and culminates with bureaucratic mass murder and the attempted annihilation of the entire Jewish population of Europe. The most familiar end of that fatal journey is Auschwitz and other industrial killing sites. For many people, that narrative provides a way to grasp the incomprehensible.

German soldiers parade in Pilsudski Square. Warsaw, Poland, October 4, 1939. Credit: Associated Press

German soldiers parade in Pilsudski Square. Warsaw, Poland, October 4, 1939. Credit: Associated PressTo support teachers and students in their learning at Facing History and Ourselves, we, too, have to learn. I often think that one of the most under-appreciated parts of our efforts is that of a translator of the work of scholars into resources for the classroom.

Shot by Shot asks us all to step back and rethink what we believe we might understand about the Holocaust. Well over two million Jews died in their own cities and towns in the former Soviet Union, murdered in open-air massacres within walking distance of their homes. Building on recent scholarship, and the opening of formerly closed Soviet archives, Joshua Rubenstein, who worked on this book while Scholar in Residence at Facing History and Ourselves, masterfully brings you into the Holocaust on the Russian Front. Beginning with an overview of the Nazi occupation of Soviet territory, Rubenstein explores the evolution of the war against the Jews. Presented in primary source documents, memoirs, and journalism from the period, generalizations about the past don’t fit here.

German infantry during the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

German infantry during the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumIn many cities and towns, mass murder came neither in stages nor after deportation. The Holocaust came shot by shot, bullet by bullet. The killers were Nazis, often assisted by local militias, and even by neighbors of the victims. Whole families were witnesses. The death camps came later and in another place. Here, the killing was face-to-face. Here, there was no cover of bureaucracy or industrial machinery. No pretenses - just outright slaughter. Human beings slaughtering other human beings.

Words we have used to understand this history blur here as well. Bystanders. Perpetrators. Victims. Rescuers. They are all useful terms, but in the history that follows, we see that these words describe actions and behaviors more often than they describe people. Some who welcomed the Nazis, and even participated in the execution of their neighbors, later turned against the Nazis and saved Jews fleeing persecution. The rigid classifications of human behavior often break down in the details.

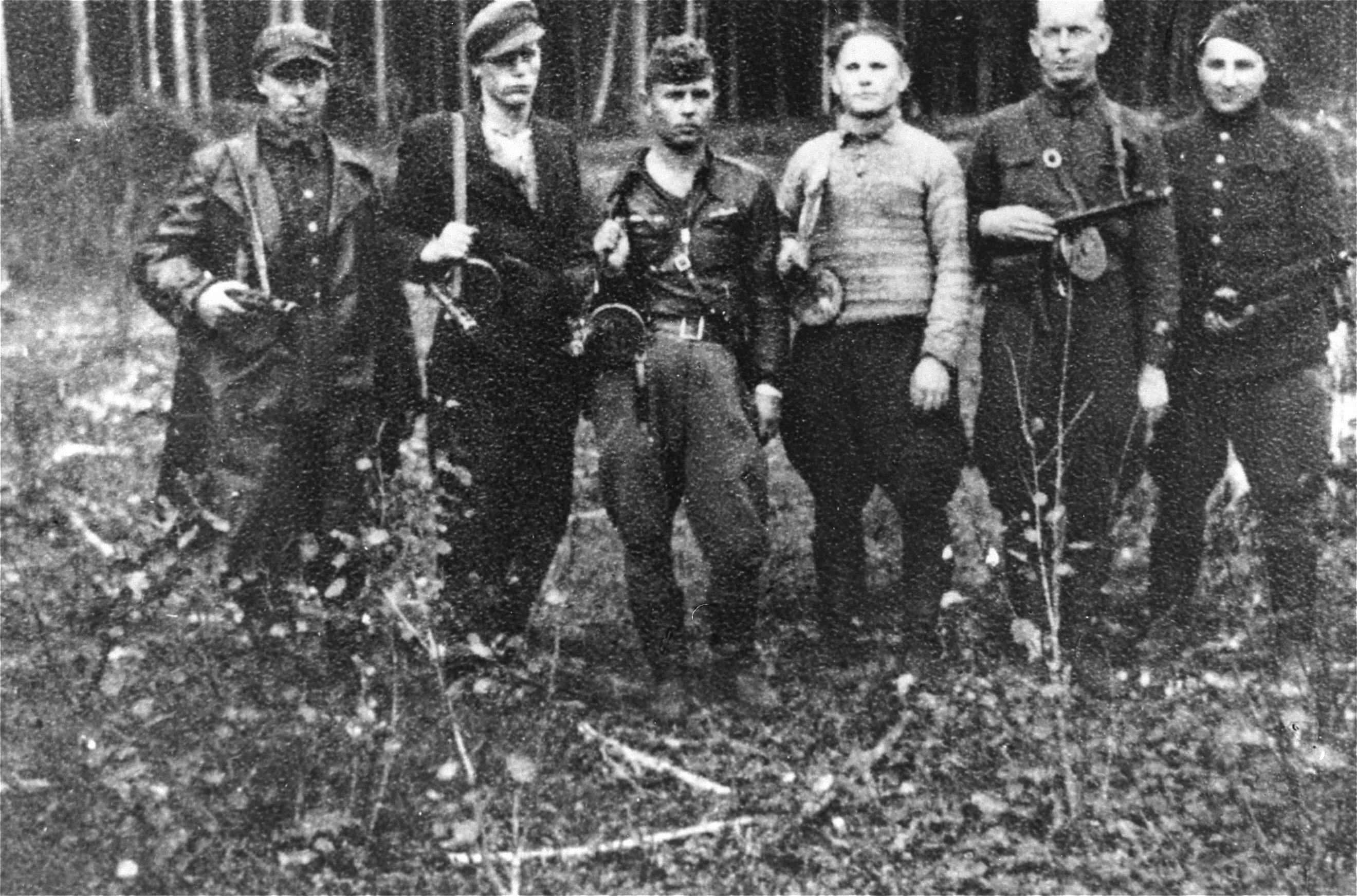

A group of Jewish partisans in the Rudnicki Forest, near Vilnius, sometime between 1942 and 1944. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

A group of Jewish partisans in the Rudnicki Forest, near Vilnius, sometime between 1942 and 1944. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumThe stories we present in Shot by Shot were, for many years, either ignored (during the Cold War) or locked up (in Soviet archives). Timing and technology have, in this resource, allowed us to bring text into conversation with video testimony from survivors, as well as several short documentaries that add perspective to the written word. We are thankful to our colleagues at the USC Shoah Foundation for helping us to make the survivor testimony available.

For the English reader, some of the names and places in this book may be difficult to pronounce, or may feel like they belong to another world. Do not allow language to distance you.

There is a particular story in this book. It is one that is worth close attention. It is the story of the destruction of Jewish life throughout Eastern Europe. And there is another story here as well. Raphael Lemkin’s warnings are worth heeding. The intimate violence reminds us of events that came both before and after the history in this book: the Armenian Genocide, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda, and Darfur.

In the 70 years since the end of the Second World War, much of the rich Jewish history of the former Soviet Union has been obscured by the destruction of the Holocaust and then Stalinist control. It is important to remember that many of the cities and villages mentioned in Shot by Shot were once places of a vibrant and diverse Jewish life, which unfolded within a multiethnic society. As readers will come to discover, tolerance can be fragile and often not resilient enough to protect minority populations in the face of murderous hatred.

Today people are beginning to unearth the stories of the past, literally digging up bones and bullets. Mass graves of disappeared populations are being marked for the first time. Facing the past is not easy. At the same time, 25 years after the fall of communism, you can hear some people explain that facing history is essential for building democracy.

Get your copy of Shot by Shot: The Holocaust in German-Occupied Soviet Territory today.