I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Julia Mayer, author of Painting Resilience: The Life and Art of Fred Terna—a new biography that explores the life of one Holocaust survivor after liberation and the skills required not just to live, but to thrive. In this interview, Mayer discusses the evolution of her lifelong relationship with Fred; vital lessons that she has learned from him about the power of lifelong learning and enduring in the face of suffering; and the continuing urgency of amplifying the stories of Holocaust survivors today.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Julia Mayer, author of Painting Resilience: The Life and Art of Fred Terna—a new biography that explores the life of one Holocaust survivor after liberation and the skills required not just to live, but to thrive. In this interview, Mayer discusses the evolution of her lifelong relationship with Fred; vital lessons that she has learned from him about the power of lifelong learning and enduring in the face of suffering; and the continuing urgency of amplifying the stories of Holocaust survivors today.

KS: How did your relationship with Fred begin and when did you know that you had to tell his life story in the form of a book?

JM: I have known Fred for most of my life through the synagogue that I grew up in and, by the time I was in my early teens, Fred and his wife Rebecca were regulars at my family holiday table. Fred had been offering since I was in my mid teens to have me come tour his studio and in 2014, I finally made those plans. Knowing him for my whole life, I've always known to ask him “is it okay to ask about your experiences today?” before posing deeper questions. Because if you've lived through that much trauma, sometimes it’s not. But we kept saying “can we ask you more questions?” and he agreed. It was the first time that we asked him about his liberation and he told us a shortened version of the story.

Fred made a comment that after he was liberated, he moved back to Prague and we were very taken aback. "What do you mean you ‘moved back to Prague’? You were 70 pounds and 20 years old and had nothing,” we thought. And that was the moment when I realized that there was more to this story. So many Holocaust narratives end at liberation and, for Fred, that's four years of what is so far a 97-year life. To lose the rest of that story, the how-do-you-move-forward story, would have been a great loss. And so that's really when I said “I think I want to write this story.” This book project with Fred started now seven years ago and that opened a whole bunch of new doors in our relationship.

KS: I'm curious about some of the stories and lessons that Fred shared with you that have been really important for you to underscore in the book that you wrote.

JM: The biggest one is that one of the things that really sustained Fred through his time in the camps and after was continual learning. He had been kicked out of school in his early teens because Jews weren't allowed to go to school in Prague by the time he was 14 or 15. But in his first concentration camp, the men who were there had all been college students so they would teach each other things. They would do this thing when they worked picking potatoes. There was a machine that would go down the rows of potatoes and it would turn the dirt up so that you could get to the potatoes that would otherwise be underground. And the men would form themselves into a “V” shape behind the machine to pick up the potatoes and they would rotate so that the man who was teaching something was at the front of the V, and then the two fastest potato pickers were right behind him. And so the man at the front wouldn't be picking potatoes; he would be teaching a lesson in something while they all worked. The two fastest potato pickers would make up for his lost potato picking time and they would rotate around so that everyone would have a chance to teach what they knew. And that was how they taught each other French poetry, calculus, and geography. Whatever subjects they knew well, they taught each other.

As much as they were exercising their minds, it was also a way of stating to each other, "There is going to be a need for French poetry in my life one day… We may not all survive this, but some of us are going to survive this and if we do, we've got to know calculus and we've got to know geography and we've got to keep moving ourselves forward." And that really was something he carried with him through all of the camps that he was in, and that has continued to sustain him.

Fred says: "My experience is what happened to me. It's there, and I can't make it go away. I just have to live with it. The camps are a bass playing inside of me. It is always there. I've learned to play the fiddle over it, not because that drowns it out, but because it creates some harmony in my life. Art is one of my fiddles." I think that's the other lesson that I associate with him. You can't forget traumatic experiences. You can't pretend that they're not there. But what are the things that you can play on top of that to create harmony? For him, that's creating artwork. That's not going to be true for everyone, but I think that finding what those things are is really important for anybody who's trying to manage any kind of trauma.

KS: As someone who spent the latter half of your twenties working on this book, I'm curious about your thoughts on the importance of younger people amplifying the stories of survivors.

JM: As part of my research for this book, Fred gave me all of his letters that he wrote to his family members each year around the holidays and so it was like a twenty-five-year archive. He would write things like “Daniel tried hockey, then he tried skiing” or “Rebecca changed jobs a couple of times.” It's a pretty normal existence. But one of the themes that runs throughout is how frequently he says that he is concerned about impending fascism. It comes up during the Bush administration and it comes up when Trump is elected.

As I went back through his materials and our conversations even further, I saw how frequently this was a concern. I could see that Fred is always afraid that this is coming. He's always looking for it. He's always checking in the rearview and asking: Does this seem familiar?

Fred is in very good shape and is very healthy at 97 years old—and he's not going to live forever. Every year, there are fewer and fewer survivors of this particular genocide among us.

And that means that they can't be the ones looking around to see whether we're safe, to see whether a revolution is necessary, and to see how we need to respond politically.

That means that we need to be doing it because if we aren't, then no one is. The generation of people who have lived through it is dwindling quickly. It's on all of us to take that responsibility forward and to be sure that we are taking care of our communities in a way that doesn't allow this to happen again.

--

Facing History and Ourselves invites educators to use our seminal case study Holocaust and Human Behavior and our accompanying classroom materials.

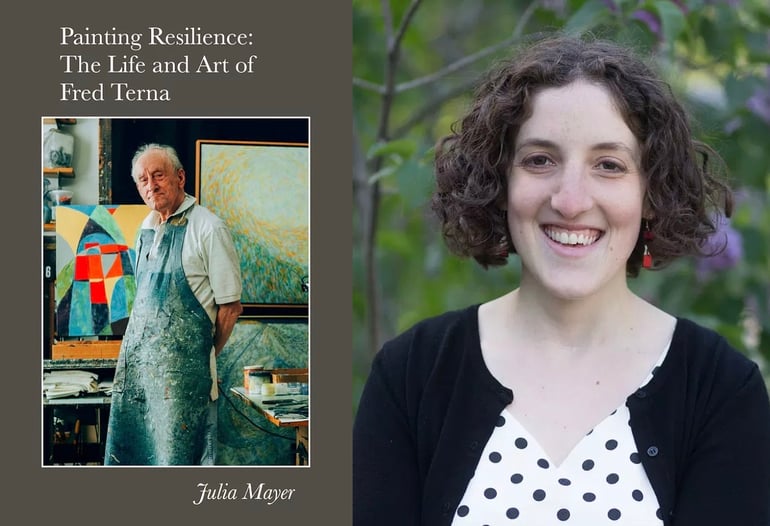

Pictured above: Artist Fred Terna on the cover of the book Painting Resilience with author Julia Mayer.