On July 2, Elie Wiesel - Holocaust survivor, Nobel Laureate, writer, political activist, and professor - passed away at 87 years old. He committed his life to keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive because he understood the dangers of history repeating itself. Now, in honor of his memory, we share a story of a second-generation Holocaust survivor who is passing on her mother's legacy one hug at a time.

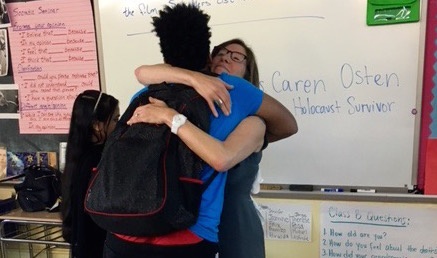

Caren Osten hugs one of the students at Ellis Prep Academy in the Bronx.

Caren Osten hugs one of the students at Ellis Prep Academy in the Bronx.

“If anyone would like a hug, please come up to the front of the room,” I announced to the class of 30-plus eighth graders at I.S. 254 in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. Silence fell upon the previously antsy and animated kids. Did they think I was joking? Why was I, a total stranger, inviting them to embrace me after recounting my mother’s experience as a hidden child during the Holocaust? Realizing how strange my comment must’ve sounded I added, “When my mother used to speak in classrooms, like yours, she always offered the students a hug afterwards, and now that I am sharing her story, I would like to continue her legacy.” The awkward silence broke when an African-American boy nearly a foot taller than I, hopped off the library table where he’d been perched and came up to wrap his long, skinny arms around me. A throng of students then rushed forward—the buzz in the classroom amplifying from the sounds of moving chairs and shifting desks—and I enveloped each one of them in my arms. It was at that very moment, as they mumbled their thanks before setting off to their next class, that I understood my mother’s magic. Open, warm, and deeply sensitive, she enabled students to understand her painful childhood struggles and the survival that followed. She used emotion to connect, and then she sealed the deal with a physical gesture—a human touch.

As a child, an adolescent, and even a grown woman, my mother and I often hold hands. Holding hands with other women—friends or relatives—was a French custom my mother held onto in America. It never seemed strange or embarrassing to me, as I knew nothing other than the simple act of my mother taking my hand in hers—walking down the street, watching a movie, or sitting in the car. It’s a ritual I share with my own two daughters.

While preparing for another Facing History classroom at the ELLIS Preparatory Academy in the Bronx, the teacher mentioned in advance that her 10th grade students were not native English speakers. They had just completed a Facing History unit on the Holocaust and I would come into their class to bring my mother’s story to life. For my presentation, I decided not to read from my mother’s memoir, Don’t they Know the World Stopped Breathing?, and focus instead on the visuals—photos and a video—which I display through a slideshow.

As the students barreled into the classroom on a hot spring afternoon, I realized this may be more challenging then I’d expected. The kids were a real international mix, coming from places like Mali, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Yemen, some of them refugees. During a brief video that recounts my mother’s story—featured on a TV episode of “20/20” about hidden children— some of the kids looked restless in their seats, others dozing or distracted. I wasn’t sure whether I’d be able to pull them in, to engage them enough so that they could understand that my mother, too, was a foreigner in a strange place when she arrived in America in 1950. That like them, English was not her first language—and only one of the many challenges she faced upon arriving in a new country.

After showing them photos of her life before and after the war, I explained what it was like for me to grow up with a Holocaust-survivor mother and grandparents who survived concentration camps. I shared that my mother tried to protect me from her sadness, but deep down I always knew it was there. Some of the students asked me questions—about religion, my mother’s health, and me.

“How do you feel when you tell your mother’s story?” one boy asked. I looked at him and paused. No one had ever asked me about my feelings, I explained, and I was grateful that he had. “After all these years, I am still deeply sad when I talk about my mother’s childhood,” I said, my eyes welling up with tears. “She suffered from circumstances that she could not understand, maybe like some of you, and that still hurts me.” They were all focused on me now.

When the teacher nodded that it was time to end our session, the students burst into loud applause. “Wait one minute,” I announced. “If anyone would like, I invite you to please come up and give me a hug.” One teacher then simulated a hug with his arms, in case anyone didn’t understand—or believe that I was actually making this bizarre offer. After a couple of seconds, Oscar, a Dominican boy stood up, approached and held me tight. The rest of the class stood in line to do the same.

This fall, Facing History and Ourselves will launch a revised version of our seminal case study, Holocaust and Human Behavior. In celebration of our 40th anniversary, this new edition offers full digital access for educators to a vast array of new scholarship, primary source material, and a wealth of images, videos, and audio never before compiled in a single resource, that are ready for classroom use.

Stay tuned to learn more!