For that reason, among others, I am looking forward to the national conversation Selma raises when it opens in theaters across the United States this week. The issues the 1965 Selma campaign raised are all too familiar today: voting rights, the shooting of an unarmed man by a state trooper, the efficacy of protest, and the role of politicians in movements for social change.

In the run-up to the release of Selma, there also has been a lot of conversation about who exactly was responsible for the political shift and resulting legislation. What role did activists play? What role did the president play? A careful study of this history reveals that a diverse group of constituents—members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), individuals (white, black, Jewish, Northern, Southern, and many others who pushed for change), and activists including John Lewis, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Hosea Williams—all came together to create the conditions that allowed American President Lyndon Baines Johnson to rally popular and political support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

What is so often lost in the teaching of the march, and what makes its particular history so compelling, is that it was the collective actions of these groups and individuals, from a variety of backgrounds and philosophies, that together pushed politicians into creating one of the defining pieces of legislation of the 20th century.

Too often, a study of this history is disconnected from an understanding of the larger goals and strategies of civil rights leaders. Historical events, like the march in Selma, often are taught as dates on a timeline, before one event and after the next, leaving students with a sense of historical inevitability. In a Facing History and Ourselves classroom, educators emphasize the importance of slowing down the study of history and exploring the choices made by people in the past, as well as consequences of their actions. Indeed, many civil rights leaders were quite intentional. They made strategic decisions based on principles in addition to lessons they drew from their own successes and failures.

In his autobiography, Dr. King explained:

The goal of the demonstrations in Selma, as elsewhere, is to dramatize the existence of injustice and to bring about the presence of justice methods of nonviolence. Long years of experience indicate to us that Negroes can achieve this goal when four things occur:

- Nonviolent demonstrators go into the streets to exercise their constitutional rights.

- Racists resist by unleashing violence against them.

- Americans of conscience in the name of decency demand federal intervention and legislation.

- The administration, under mass pressure, initiates measures of immediate intervention and remedial legislation

The original focus of civil rights activists in Selma was voter registration, not the march from Selma to Montgomery. Before the march, in the first few weeks of 1965, SNCC and local activists intensified their campaign to register black voters. Local black leaders asked the SCLC to join the campaign in Selma to protest discriminatory voting practices.

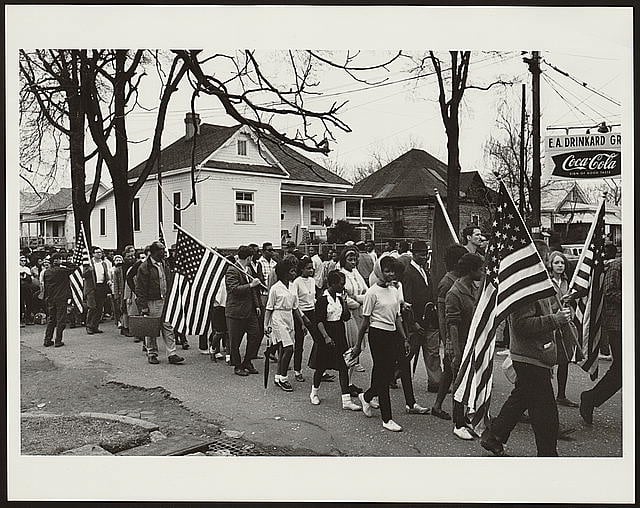

Participants, some carrying American flags, marching in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Participants, some carrying American flags, marching in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. Photo courtesy of the Library of CongressSelma Sheriff Jim Clark responded to the nonviolent protests with physical force. In response to the arrest of an SCLC activist, protesters held a nighttime rally on February 18 at the Zion United Methodist Church in the nearby town of Marion, Alabama. The rally was entirely peaceful until the crowd left the church. Then, seemingly mysteriously, the streetlights went out and a mob of white segregationists and police assaulted the protesters. One of their victims was 26-year-old army veteran Jimmie Lee Jackson, who died from his injuries a few days later. In the aftermath of events in Ferguson, Missouri, and New York City late last year, it's interesting to read James Bevel's recollections about how activist leaders struggled to find a way for the community to constructively express their grief and outrage. In an interview for acclaimed civil rights documentary Eyes on the Prize, the reverend and SCLC strategist explains:

"If you went back to some of the classical strategies of Gandhi, when you have a great violation of the people and there's a great sense of injury, you have to give people an honorable means and context in which to express and eliminate that grief and speak decisively and succinctly back to the issue. Otherwise the movement will break down in violence and chaos. Agreeing to go to Montgomery was that kind of tool that would absorb a tremendous amount of energy and effort, and it would keep the issue of disenfranchisement before the whole nation."

It is easy to imagine that without Bevel's insights, events could have played out much differently. Instead SCLC leaders scheduled the march from Selma to Montgomery for March 7. Local law enforcement met the peaceful protesters with unimaginable brutality. By the time the attack was over, nearly 60 marchers had gone to a local hospital with injuries, including John Lewis, whose skull was fractured. Later that evening, the ABC television network interrupted a national broadcast the documentary Judgment at Nuremberg—a film about Nazi racism—to show the shocking footage of police in Alabama attacking American citizens.

"The film was interrupted several times to interject updates and replays of the violence in Selma, and many viewers apparently mistook these clips for portions of the Nuremberg film," SCLC lieutenant Andrew Young, who was on the ground that day, recalls in his memoir An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America. "The violence in Selma was so similar to the violence in Nazi Germany that viewers could hardly miss the connection."

The day became known as Bloody Sunday.

John Lewis recalled the public outcry in the aftermath of the march in his book Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement:

"During the first 48 hours after Bloody Sunday, there were demonstrations in more than 80 cities protesting the brutality and urging the passage of a voting rights act. There were speeches on the floors of both houses of Congress condemning the attack and calling for voting rights legislation. A telegram signed by more than 60 congressmen was sent to President Johnson, asking for 'immediate' submission of a voting rights bill."

After Bloody Sunday, President Johnson took action. On March 15, 1965, he addressed both houses of Congress about the urgent need for new legislation. Johnson concluded what many consider his finest address by echoing the famous refrain of civil rights activists, "we shall overcome."

What a close study of the events in Selma reveals is that those involved were, in Facing History terms, "Choosing to Participate"—exercising their voices to make active, conscious choices to take part in their local, national, and global communities. A healthy democracy requires citizens who understand that history is not inevitable, and looking at the events before, during, and after Selma illustrates just how ordinary people shape history.

Indeed, people make choices and choices make history.

We suggest the following resources and guiding questions for teaching and talking about the events in Selma:

- What was the relationship between the goals of activists in Selma and the choices they made?

- How did nonviolent direct action force people in Selma and around the country to assess their accepted customs? What role did the press play?

- How effective were the nonviolent tactics in Selma? How did they help reshape American democracy?

- How did the choices make by activists, ordinary people, and authorities in Selma influence the choices of politicians?

Below are resources to take the conversation further:

Register to download a free copy of Facing History's study guide, Eyes on the Prize. To go deeper into the Selma events, read Chapter 6 of the guide and explore the following key documents:

- Memories of the first march from Selma to Montgomery and Bloody Sunday [p. 87]

- Excerpts from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s autobiography [page 90]

- The speeches of President Johnson [page 93]

Help students learn about voting rights and nonviolent protest, and review concepts related to the structure of the United States government, with the Nonviolence as a Tool for Social Change Unit.

Watch activist Linda Lowery describe marching in Selma.

Hear Congressman John Lewis discuss studying nonviolence.

A Facing History staffer in Los Angeles had the opportunity to attend an early screening of the film. Read her thoughts on Selma on our sister blog Learn + Teach + Share.

Do you teach about the events in Selma? Tell us how—comment below.