Facing History teacher Saul Fussiner shares how he addressed issues of race and police brutality with his students at the start of the new school year.

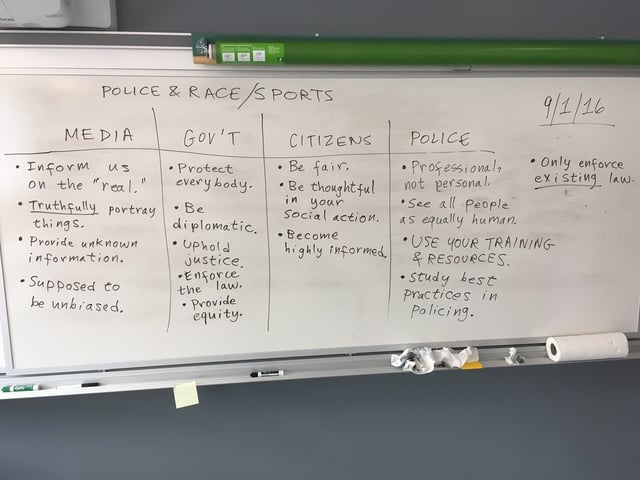

A look at Saul Fussiner's classroom whiteboard during his lesson on the intersection between race and policing.

That nervous, excited leadup to the first day of the school year. This year it started early, on July 8th, when we received a Google file from the Program Director at my school:

All,

I'm just starting to save resources on the events of the last few days, both to try to get a handle on what's happening and in anticipation of figuring out how to incorporate these events into what we teach and talk about in the fall.

This is just a gathering of resources; just thought I'd share. Feel free to add other resources as you come across them.

Meredith

When we opened it, the staff members of my school were presented with a wealth of articles and videos about the events in Baton Rouge, in St. Paul, and in Dallas. The school year was almost two months away, but this summer--like several other recent summers--was already coalescing around a familiar theme, the tortured relationship between race and policing. We already knew that many of our students would return to school--a beautifully renovated new school--feeling angry and in pain. We already knew that we were among the adults that they would turn to with this pain.

Two weeks later in the long hot summer of 2016, North Miami police shot a black man who was lying on the ground with his arms raised in surrender because the severely autistic adult in his care was holding a toy that neighbors thought was a gun. I thought of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book, Between the World and Me, where he explains that his friend Prince Jones was a man who had done everything right in his life yet was still killed by a police officer and how that outcome disillusioned Coates about the prospects for a black man in America. Now we had the ultimate image of police peril against black people: a man who quite literally could not have been telegraphing his surrender and his lack of threat any more clearly still being shot by a police officer. When asked by his victim why he shot him, the officer only said that he didn’t know.

Still later in the summer, the broken relationship between law enforcement and black communities intersected with protests by athletes against the ritual of obedience to “The Star Spangled Banner.” (It should be noted that our Program Director’s earlier list of resources also included some of this summer’s initial sports protests, such as Serena Williams’ raised fist at Wimbledon, which evoked the 1968 Olympics).

My school, New Haven Academy, is a Magnet School that draws from many school districts in New Haven county. We are a small high school with under 300 students. Sixty-five percent of our students are black, and 17% are hispanic. Locally, friction between the police and the hispanic community has been especially high, with lawsuits for police harassment and brutality in several New Haven county towns, including New Haven itself.

Meredith Gavrin, the aforementioned Program Director, and I collaborate on planning and teaching the Civics/Choosing to Participate class in our school, and this is one of the places where current events live in the building. Favoring an Inquiry approach, we decided to start the year by asking our students to tell us what they felt were the big news stories of the summer rather than hitting them with our own preconceived notions.

There was some mention made of Pokemon Go, of Selena Gomez’s health scare, and of the Louisiana flood, but my students overall chose the intersection of race and policing with sports protests as the major news story of the summer. Next, I asked students to think of the role that we must all play to make things right. I drew a four section chart on the board and the students did the same in their notebooks. The sections were called “Media,” “Government,” “Citizens,” and “Other.” I asked about the role each should play to make things better. First, the students insisted “Other” should simply be “Police.” Then, my students started to raise their hands and fill in the chart. As I copied their ideas on the board, they copied them into their notebooks.

Ideas built on other ideas. When discussing the role of the citizen, my student Javon said, “Don’t just protest.” I pressed him on what he meant by that. “Don’t just protest for protest’s sake,” he elaborated. “Be thoughtful in your social action.”

“Become highly informed,” my student Karoz added, building on Javon’s idea.

Later, as we discussed the police, one student spoke of using training and resources rather than instinctive responses. Another contextualized that as studying “best practices in policing.”

Because our students were leading the discussion, they took ownership of the activity and actually said many of the things that I say to them as they work on their own social action projects later in the school year. “Be thoughtful,” “become highly informed,” “study best practices.” Stepping back, I realized that many of the things I try to teach my students about research and social action, they could just as easily teach me and teach one another when we all take the time to simply relax, pose questions, and listen.

It’s going to be a great school year.

Facing History's new unit, "Facing Ferguson: News Literacy in the Digital Age," uses the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown as a case study to help students examine how they can become responsible consumers and producers of news and information in the digital age.