In this age of smartphones, social media, and text messaging, I sometimes ask myself when was the last time I sat down to actually talk and listen to someone. I wonder how often my students actually engage in face-to-face conversations, especially even more with someone who is older than them.

Then twice in one week I stumbled across The Great Thanksgiving Listen, first on my drive home listening to NPR and then during my Twitter check-in before bed. What was this Great Listen project? I wanted to know more.

So, I looked it up. What a wonderful opportunity to practice inquiry and discourse. I immediately saw this as a chance to empower my students to connect, converse, and listen. It is so important for young people to understand that connecting with another person goes beyond a “like” or a “heart.” If students learn how to carry a conversation, develop inquiry-based questions, and listen to the response, this skill will last and benefit them well beyond this activity. This is a life lesson that they can practice, refine, and slowly perfect.I asked my Student Leadership class if they were willing to participate. Some were all about it, others were like, “Do what?” This is when I reached out for help. How do I help young people understand how powerful a meaningful conversation with someone else can be, potentially leading to a lifelong connection and understanding?

Thankfully, there were resources out there to hook my students. I started by sharing with them David Isay’s TED Talk about StoryCorps and the power of sharing personal stories.

His talk resonated with my students and with me. Everyone does have a story. We were moved by the unexpected story that Dave uncovered about his father when he took the time to interview him, which led to a new, deeper connection with his father and a legacy he can share with his own children. We reflected as a class about this clip, and I posed a question to my students, “What is your story?”

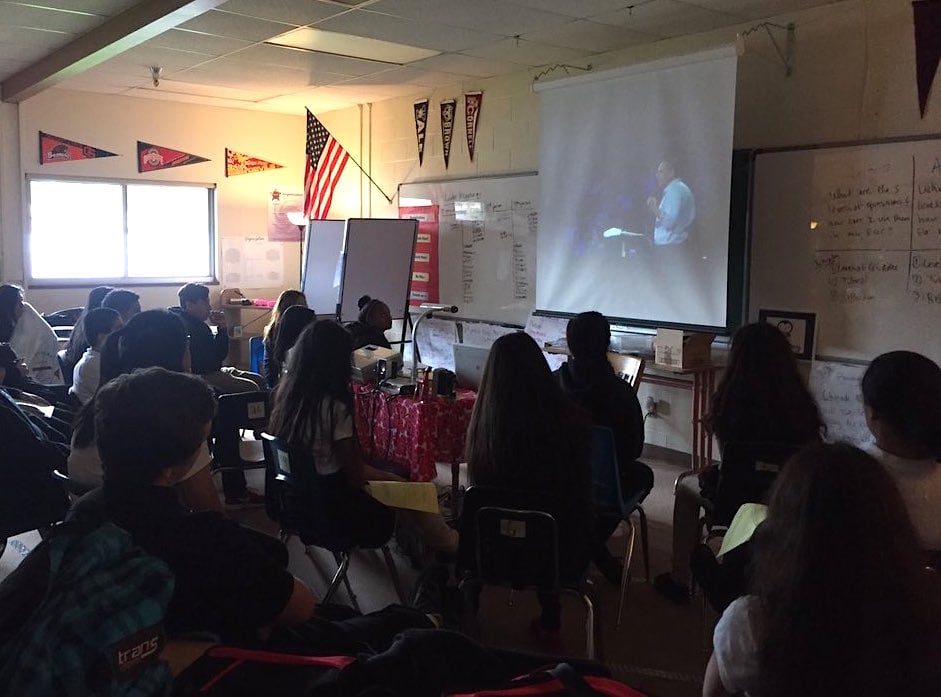

Crystal's students watching Dave Isay's Ted Talk

My students shared their stories in small groups (ranging from their first day of middle school to a memorable sports moment) and discovered how powerful it was to tell a story and, in their words, how “cool” it was to hear their peer’s story. I then asked them to think about people in their lives they were curious about. I gave them only two instructions: 1) the interviewee had to be older than them, and 2) they had to interview them face-to-face (not FaceTime) for at least 30 minutes.

Then I reached out to my Facing History network for more ideas. This network is a rainbow of resources not only for teachers. I’ve used protocols, activities, readings, and films for leading workshops, teaching students, advising students, or just personal growth. Through the network, I was able to share my thinking and experiences with Facing History staff, who in turn shared with me suggestions from the Los Angeles educator network. This was a helpful exercise to encourage my students that there are so many directions to take your interview, a topic that may feel “simple” can actually be “great.”

During the next class, students shared with their peers their interview subject. They ranged from older siblings or cousins to parents and grandparents. We then took time to brainstorm questions. We categorized the questions and then ranked them based on what could be an “icebreaker” question versus a “deeper extended” question to push the conversation. This was a difficult process for my students, one they still have not mastered, but it got them thinking.

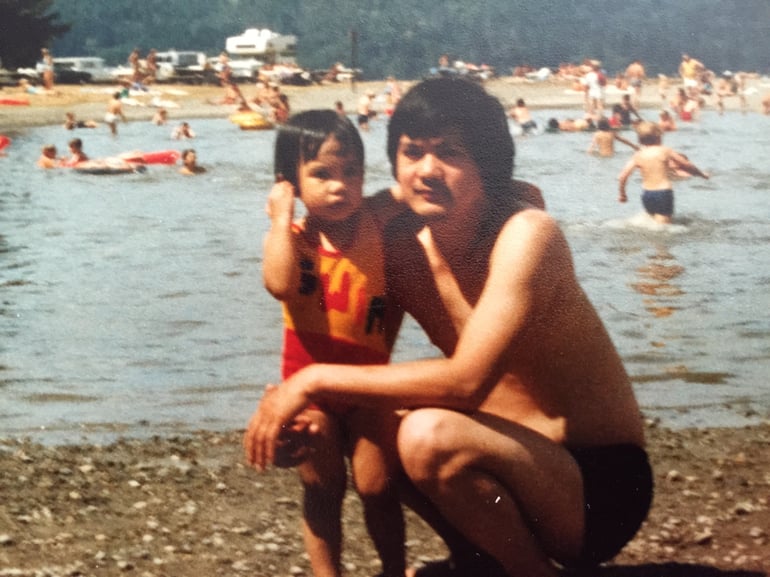

Lastly, I wanted my students to be okay with feeling vulnerable in this process. It’s not easy to conduct an interview and ask questions of an elder. So I led by example. My dad and I never talked much about his immigration story as a teenager. I would get bits and pieces of it when I was young, but never the details. So I sat my two sons down next to me, asking them to be very quiet, as I interviewed their “Lolo,” or grandfather in Tagalog. This interview was not only for me, but for my two young sons. I wanted them to hear his story too. When I was young, I was fortunate to have grandparents living with me and I would hear their stories around the dinner table every night. I wanted my boys to have that same experience with their Lolo. Like so many young people, they too are already exposed to the technology distraction and I wanted them to learn that connecting through conversation is so powerful and magical. Not only did my children and I benefit from this example, but I brought my experience into my classroom, shared with my students my vulnerability, how I drafted questions in my head, practiced saying them out loud, and then went for it. This is the beautiful result.

Crystal and her father at Lake Chelan, WA in 1980

Crystal and her father at Lake Chelan, WA in 1980

Listen to some of my student's recordings: (students were encouraged to conduct the interviews in the primary language that is spoken in their homes) Itzel's Interview, Millie's Interview, Ryan's Interview.