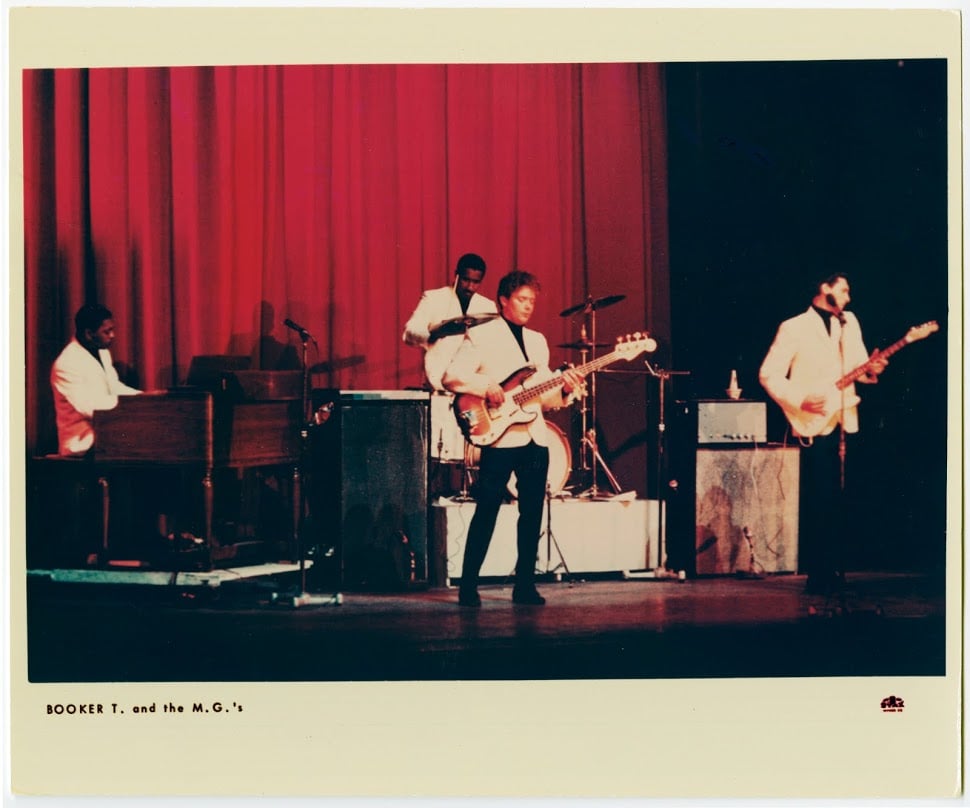

Welcome to the second installment of our four-part blog series exploring the connections between music, history, and social change. In this second lesson, students will be introduced to Booker T & the MGs, who were the house band for many Stax Records artists, in addition to being an independent act.

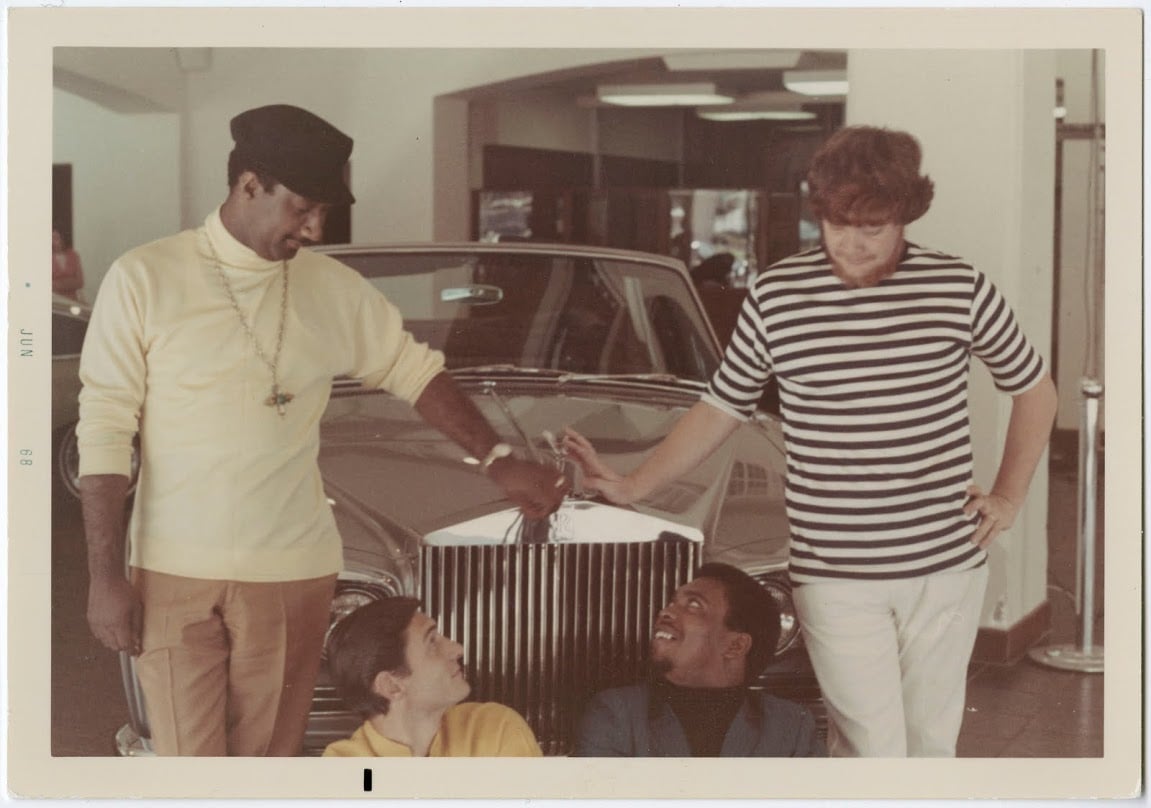

Despite performing in an era when Memphis and much of the American South was segregated, Booker T & the MGs was a racially integrated band.

Stax co-owner Al Bell described the unique business environment at Stax that made it possible for two white men to play with two black men in the South during the 1960s:

"I was amazed to sit in the same room with this white guy [Stax co-owner Jim Stewart] who had been a country fiddle player…We had separate water fountains in Memphis and throughout the South. And if we wanted to go to a restaurant, we had to go to the back door—but to sit in that office with this white man, sharing the same telephone, sharing the same thoughts, and being treated like an equal human being—was really a phenomenon during that period of time. The spirit that came from Jim and his sister Estelle Axton allowed all of us, black and white, to come off the streets, where you had segregation and the negative attitude, and come into the doors of Stax, where you had freedom, you had harmony, you had people working together. It grew into what became really an oasis for all of us."

This was especially significant in the racially-segregated city of Memphis. When 13 black 1st-graders were allowed to attend formerly all-white schools—nearly a decade after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that said public schools must integrate—many white families took their children out of those schools. In 1968, black sanitation workers went on strike because they endured worse working conditions than their white counterparts.

Lewis Steinberg, original bassist for Booker T and the MGs and a writer of "Green Onions," described the contrast between the Stax studios and the outside world:

"We integrated Stax and didn't think no more about it than the man on the moon. We couldn't go and play on the same bandstand together in Memphis! But we'd get together inside the studio and do everything we want to."

After Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis in April, 1968, tensions in the predominantly-black neighborhood surrounding Stax heated up. The riots that followed included arson attacks on a number of white-owned businesses, but neither the Stax studios nor the Satellite Record Shop next door to the studio was touched. The toll from King's murder took a different form:

"It had a tremendous impact," Jim Stewart said. "It kind of put a wedge, or at least opened up that suspicious element, [within] the company. Although we tried to bond together and continue to work together, from that point on it changed considerably. There wasn't that happy feeling of creating together. There was something missing. You couldn't quite put your finger on it, but you knew things had changed and there's no way you could go back. Everybody started withdrawing, pulling back from that openness and close relationship that we felt we had...While we were in the studio I don't think that was ever affected, but once we were through, everybody went their separate ways. There wasn't that mixing and melting together like we had before."

"It heightened internally the racial sensitivity amongst those of us at Stax," affirmed Al Bell. "Up to that point in time I don't think we focused in on that much. Dr. King's death had a tremendous impact at Stax. We were there in the middle of the black community and here we were an integrated organization existing in a city where integration was an issue. Dr. King's death caused [some] African-American people in the community to react negatively toward the white people that worked for Stax Records. Immediately after [King's] death we had to protect some of the white people who worked at Stax."

Saxophonist Floyd Newman, a regular session player with the MGs, shrugged off talk of tensions invading the studio. He explained that the anger so many saw in the neighborhood and across the country "didn't destroy us. It didn't separate us. We were together. We could take care of that [because] nobody stressed about, wasn't [anybody] thinkin' about [any] black, white, green, purple. None of that. We just had a fantastic relationship working at Stax. Musicians, we were together."

The group continued to play together until 1970, when Booker T. left the band.

Invite students to watch a video of Stax Music Academy performing a Booker T & the MGs hit, "Green Onions":

Then answer the following questions:

- What does it mean to belong to a group? How does a person know when he or she belongs?

- How does group membership shape the way we see the world and the way the world sees us?

- What are the conditions that make integration possible, and what gets in the way?

- What societal pressures did the members of Booker T. and the MGs have to confront?

- What were some specific challenges the band faced?

- How did the band persevere despite the racial tensions of the time?

Go Deeper:

- Find historical images of Booker T and the MGs.

- Watch Booker T Jones, Steve Cropper, Al Jackson, and Al Bell discuss the family that grew as a result of the music.

- Download Facing History’s The Sounds of Change: An Educator's Guide to Visiting the Stax Museum of American Soul Music for lesson activities, media resources, and Common Core connections.

The lesson plans and videos are part of Facing History and Ourselves' latest teaching resource, Sounds of Change, published in partnership with the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis, Tennessee. The resource's text-dependent questions that accompany both the lyrics and the historical documents are based on the Common Core Anchor Standards for Reading and Literacy in Social Studies. In addition to measuring student understanding of the material covered, the questions will prepare students for the types of questions they will encounter on Common Core State Standards–aligned assessments. Stay tuned next week for our third installment: Respecting Self and the Other.

Do you use music to teach about racial identity? Tell us about it—comment below!