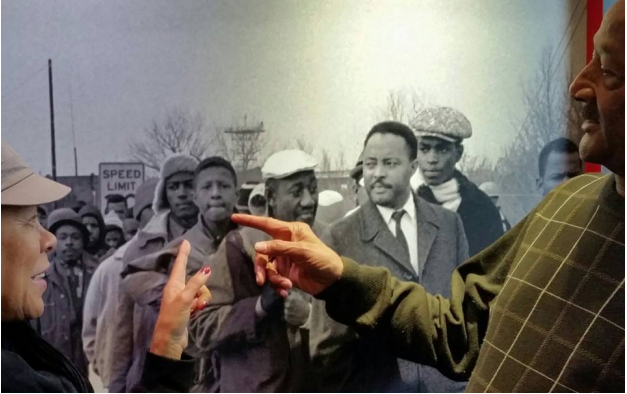

On March 7, 1965, 17 year old Charles Mauldin took his place near the front of a line of marchers heading out of Selma, Alabama with a demand for equal voting rights. The peaceful marchers were brutally assaulted by local law enforcement; Mauldin was so close to John Lewis that he still remembers the sound of an officer’s billy club cracking Lewis’ skull. The drama of the Selma to Montgomery march transfixed Americans and was a pivotal moment in the struggle for civil rights. In 2015, the 50th anniversary of the march, Mauldin looked back at his experiences, including at photos of him at the march. Now, as student activists are drawing national attention with their calls for reform in the wake of the Parkland school shooting, Charles Mauldin reflects on the power of young people to spark social change and offers his insights for today’s emerging activists.

How did you get involved with the Civil Rights Movement? What got you started as an activist?

I didn’t start off as an activist. I started off as an observer of little incidents that came into my life from being in a segregated environment. We were taught to call older people “Mr.” and “Mrs.” but I saw white people half or one-third the age of my mother and father calling them by their first names and they didn’t say, “yes sir” or “no sir.” Little things like that grated on me. And then Bernard Lafayette came to town in 1963 and he began to ask simple questions: “Why can’t your parents vote?” Or, “Why can’t you drink out of the white water fountain? Why can’t you use the bathrooms in the stores downtown?” Little questions like that left me puzzled. I had no answer. We’d been brought up in an environment where we didn’t think outside of the box because it was too dangerous. It was the job of the state, the county, and the local police department to basically keep us contained.

But Bernard Lafayette sort of piqued our curiosity and we realized that anybody in my community who was black had one form of indignity or another heaped upon them, each different but we all shared being discriminated against and suffered indignities day in and day out. When I got in the movement I began to realize the political and the human solution to our situation was through non-violence. And once I recognized that, I became involved in marches and demonstrations. I became the head of the Lowndes County Youth League in mid-1964 and, from that point, we marched almost every day until later in 1965, culminating in the march to Montgomery. I hardly spent any time in school in all of 1965. We basically took the year off to be involved in demonstrations. I started off at 16 and was 17 during the march to Montgomery.

How did it matter that young people were at the forefront?

It made an impact in almost every major movement. It was young people in Montgomery who helped to win the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Young people in Birmingham who provided the leadership in the Birmingham movement. It was the young people in Selma who sustained the movement until the adults showed up. Young people in South Africa who helped with the liberation there. Young people are always a fire that causes change.

I think it’s because they don’t have the disadvantage of being overexposed to what the consequences of their actions could be. They respond more innocently to the issues at hand and they don’t have the restraints on them that adults have, like paying bills or losing jobs. Just as in Florida right now, they are responding passionately to an issue they see that is vital to them, and the response is simply open honesty.

How do you stay persistent when progress is slow to come?

When a movement gets created, it’s because there’s something inherent in how people respond. They’re not responding to circumstances outside of themselves, they’re responding to a circumstance that involves them and they have a personal commitment and a personal involvement, so it’s real to them. It’s not external, it’s internal and that’s what I think motivates them. That’s what was true for us. The issue [of school violence] is not going to go away and it’s in the fabric of [the Parkland students’] lives now. And I think that’s a self-sustaining type of situation.

What do you want today's young activists to know? What advice do you have for them?

You have to take one step at a time, day by day. John Lewis once said, “Find ways to get in the way of what is wrong in life.” Injustice, discrimination, racism, and now gun violence. Find ways to get in the way of what you see as wrong. And realize that you don’t have to be extraordinary to change the world. You just have to do ordinary things on a constant basis. Stand up each day.

Do you have questions about the best way to address Parkland with your students? Join us on March 20 for our webinar, "Student Agency After Parkland," to discuss the issues educators are facing in the wake of the most recent school shooting. From how to help your students reflect on the violence in their own communities to talking about student protests and walkouts to the controveries surrounding gun control, we'll help you determine how to navigate these difficult topics in the classroom.