Next week marks the 51st anniversary of the assassination of American President John F. Kennedy. We can explore his legacy by examining the Kennedy administration's responses to the civil rights movement, and how these responses changed over time. The 1961 Freedom Rides, when civil rights activists rode public buses through the American deep South to challenge segregation policies, is a powerful example and case study through with to look at this change.

Kennedy took office in late January 1961, the youngest U.S. president ever to be elected to office.

The Freedom Rides presented a dilemma for the new Kennedy administration. Were these leaders prepared to face the political risks of standing up for civil rights? In the PBS American Experience film Freedom Riders, journalist Evan Thomas points out that the civil rights issue was not one that President Kennedy and his brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy had chosen to spotlight as they tried to usher America into a new era. As Thomas notes,

"The Kennedys, when they came into office, were not worried about civil rights. They were worried about the Soviet Union. They were worried about the Cold War. They were worried about the nuclear threat. When civil rights did pop up, they regarded it as a bit of a nuisance, as something that was getting in the way of their agenda."

One of the first governors to support President Kennedy prior to his election was John Patterson, a segregationist from Alabama. In a biography of the governor, historian Warren Trest describes Patterson's great admiration for Kennedy, both politically and socially. In fact, Patterson believed that Kennedy would be sympathetic toward the issue of segregation:

"The governor could not have been more open about his reason for being first on the Kennedy bandwagon. He genuinely liked John Kennedy, both as a person and as a public figure. Convinced that JFK would be the next president of the United States, he wanted Alabama to have a friend in the oval office."

On May 15, 1961, President Kennedy learned of the attacks on the first two buses of Freedom Riders in Anniston and Birmingham, Alabama. For the president, the timing was terrible: In less than two weeks, he was to hold a summit with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who would surely use the story for his own purposes.

Nevertheless, the Freedom Rides forced the Kennedy administration to confront the issue of white resistance to integration. In Freedom Riders, civil rights activist Julian Bond recalls that the Freedom Rides made it suddenly necessary for the administration to focus on domestic affairs.

"For the Kennedy brothers, domestic affairs were an afterthought...and the civil rights movement was an afterthought beyond an afterthought," he explains. "Now all of a sudden, chaos is broken loose. Attention is riveted. People are talking about this. The whole world is watching."

The negative attention that these events swiftly generated worldwide presented a dilemma for the Kennedys. If they enforced federal law, they risked losing their supporters in the South, especially Governor John Patterson. If they didn't enforce the law, damaging images and evidence of civil strife were sure to be used by opponents inside the country and enemies outside.

Outraged by both the violence and the violent images making headline news across the country, President Kennedy wanted the Freedom Rides to stop, or at least be delayed. The bulk of the responsibility for the Freedom Riders fell to the attorney general, Robert Kennedy. He was charged with doing what he could to make the crisis go away. Robert Kennedy asked his longtime friend, Justice Department representative John Seigenthaler, to mediate between the Freedom Riders and southern politicians. A native of Nashville, Tennessee, Seigenthaler had local roots that Robert Kennedy hoped would help ease tensions with southern politicians. In the film, Seigenthaler recalls, "I'd go in, my southern accent dripping sorghum and molasses, and warm them up."

His first task was to get the CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) Riders safely on airplanes to New Orleans, where they planned to celebrate the anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing segregation. When the Riders arrived safely in New Orleans, Seigenthaler thought both the Freedom Rides and the crisis were over. Instead, he learned that Diane Nash and others from the Nashville Student Movement planned on finishing what the CORE Riders had started. In the film, Seigenthaler remembers that pivotal moment:

"I went to a motel to spend the night. And you know, I thought, 'What a great hero I am...you know? How easy this was, you know? I just took care of everything the president and the attorney general wanted done. Mission accomplished."

My phone in the hotel room rings and it's the attorney 'eneral. And he opened the conversation, 'Who the hell is Diane Nash? Call her and let her know what is waiting for the Freedom Riders.' So I called her.

I said, 'I understand that there are more Freedom Riders coming down from Nashville. You must stop them if you can.' Her response was, 'They're not gonna turn back. They're on their way to Birmingham and they'll be there shortly.'

You know that spiritual [song]—'Like a tree standing by the water, I will not be moved'? She would not be moved. And...I felt my voice go up another decibel, and another, and soon I was shouting, 'Young woman, do you understand what you're doing? You're gonna get somebody...Do you understand you're gonna get somebody killed?'

And there's a pause, and she said, 'Sir, you should know, we all signed our last wills and testaments last night before they left. We know someone will be killed. But we cannot let violence overcome nonviolence.' That's virtually a direct quote of the words that came out of that child's mouth.

Here I am, an official of the United States government, representing the president and the attorney general, talking to a student at Fisk University. And she, in a very quiet but strong way, gave me a lecture."

If they couldn't stop the second round of Freedom Rides, the Kennedy administration could at least stop the violence. In an effort to enlist the help of local law enforcement, Seigenthaler and the Kennedys sought the support of Governor Patterson. Negotiations with Patterson were difficult. He blamed the Riders for the situation, not the violent mob. Furthermore, he was not willing to risk the political consequences of being seen as supporting the Riders.

Without the cooperation of local law enforcement, the president's advisers suggested sending in the army or the National Guard. Hoping to avoid direct intervention, the president called Governor Patterson. Patterson refused to take the call, however, claiming to be on a fishing trip. When Seigenthaler was finally able to meet with the governor, Patterson claimed that the stand he was taking made him more popular than the president. Despite this talk, Seigenthaler left believing that Patterson would ultimately accept his responsibility and allow the Freedom Riders to leave the state safely without the need for federal intervention.

He was wrong.

When the Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders arrived at the Montgomery station, there wasn't a single policeman to be found. The Riders entered the station cautiously, prepared to speak to the

members of the press who were there to cover the event. Within minutes, a violent mob overtook the station, mercilessly beating the Riders, the press, and even Seigenthaler, who was there to

meet the Riders.

The next day, Robert Kennedy called for federal intervention.

In his book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, Raymond Arsenault explains:

"Robert Kennedy did not like the idea of alienating the voters of a state that had just given his brother five electoral votes, but he was running out of patience—and options. Though politically expedient, relying on state and local officials to preserve civic order was too risky...[President Kennedy] saw no alternative to a show of real federal force in Alabama. With the summit [with Soviet Premier Khrushchev] less than two weeks away, he simply could not allow the image and moral authority of the United States to be undercut by a mob of racist vigilantes, or, for that matter, by a band of headstrong students determined to provoke them."

As the activists' efforts progressed, Robert Kennedy became more invested in the Freedom Rides and civil rights.

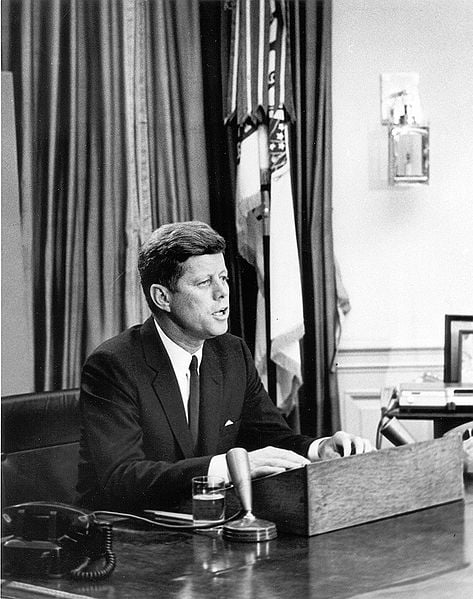

White House meeting with civil rights leaders on June 22, 1963. Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

White House meeting with civil rights leaders on June 22, 1963. Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records AdministrationOn May 29, 1961, the attorney general committed himself fully to the Freedom Riders' mission by directly petitioning the Interstate Commerce Commission for the enforcement of integration in interstate travel.

His petition outlined the number of facilities that were still maintaining segregation and cited the Supreme Court rulings of Morgan v. Virginia and Boynton v. Virginia, which together outlawed segregation on interstate buses and in related facilities. He explained, "It is the unquestioned right of all persons to travel throughout the various states without being subjected to discrimination."

The Kennedys' response to the Freedom Rides resulted in the alienation of one of the administration's first and strongest supporters, Governor John Patterson. On June 3, 1961, Patterson

wrote the president:

"It is with grave concern that I warn you of further disorder and discord which is bound to result if these subversive-minded agitators continue to deliberately harass the people of the South, by nationwide television these trouble-hunting meddlers have now openly solicited support among racial extremists for an all-out 'invasion' of Mississippi, our sister state.

This brazen plan is but the latest in a series of premeditated schemes to taunt the southern people, foment racial strife and embarrass our nation. May I remind you that the South is perhaps the most patriotic region of the United States? We are proud of our heritage, but we are alarmed to see the federal government seemingly acting in concert with those at the root of current unrest in the South.

I call on you to see your good office to stop this planned 'invasion' of our section. With the persuasion and influence of your office, you can do this nation a great service by urging all the rabble-rousing outsiders now in the South to leave at once and all other do-gooders to stay at home.

If you are really interested in using the powers of your office in the best interests of all the people, if you are really interested in promoting good relations, then I believe you will make a public pronouncement castigating these self-appointed agitators. In the interest of public tranquility, I beseech you to act now to save the nation from further strife and discord. It is time for a 'return to reason' on the part of the federal government in dealing with this explosive issue."

Journalist Thomas asserts that the Freedom Rides changed the way the Kennedys thought about racism and civil rights. By June of 1963, President Kennedy would call for legislative action to enforce civil rights, publicly embracing the cause in no uncertain terms:

"A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all. Those who do nothing are inviting shame as well as violence. Those who act boldly are recognizing right as well as reality."

Thomas believes that "there's a direct line from the Freedom Riders to the speech that President Kennedy gave in June of 1963, calling on Congress to pass legislation to get rid of Jim Crow and to give

civil rights protection to all citizens.”

Keep The Conversation Going: Connection Questions

1. What political risks did the civil rights movement present for the Kennedy administration?

2. If you were one of the Kennedy brothers, how would you respond to Diane Nash's demand that "we cannot let violence overcome nonviolence"?

3. How did civil rights activists hope to change the Kennedys' political calculations?

4. If you were President Kennedy, how would you have responded to Governor Patterson's letter?

5. President Kennedy told the public, "A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all." What can political leaders do to make social change “peaceful and constructive for all"?

Go Deeper:

Watch the PBS American Experience documentary Freedom Riders

Find resources to explore the civil rights era

How do you teach about the legacy of John F. Kennedy? Comment below.