When I was a teenager, I traveled to Auschwitz on a Jewish summer program. Since I played the saxophone, I was asked to perform the song “Eli, Eli” for a memorial service. It is a popular Jewish song my father made me sing every night before bed but I knew nothing of its origin. My tutor told me as I walked to the stage that Hannah Senesh, who wrote the poem on which the song is based, was a Hungarian-born, Palestine-based paratrooper who died trying to rescue Hungarian Jews during the Holocaust.

When I was a teenager, I traveled to Auschwitz on a Jewish summer program. Since I played the saxophone, I was asked to perform the song “Eli, Eli” for a memorial service. It is a popular Jewish song my father made me sing every night before bed but I knew nothing of its origin. My tutor told me as I walked to the stage that Hannah Senesh, who wrote the poem on which the song is based, was a Hungarian-born, Palestine-based paratrooper who died trying to rescue Hungarian Jews during the Holocaust.

This performance was incredibly formative for me: for the first time, I performed “Eli, Eli” imbued with the courage and pain of Hannah Senesh’s memory and with the song’s heavy meaning—the existential threat the Holocaust posed for Jews around the world. As I performed, I began to empathize with Senesh’s fear and resented that she was forced to experience such profound hatred and loss.

During April, Genocide Awareness and Prevention Month, consider how music can inspire students to approach the study of mass violence with depth, compassion, and empathy.

I started to think about this last month when Julian Saporiti and Erin Aoyama, a duo who created the musical project, No-No Boy, shared how they are exploring the role music can play in the classroom at the Facing History Partner Schools Network Conference. Using their research in Asian-American history, they uncover narratives in archives that have historically been marginalized. Saporiti then uses that research to compose songs that provide listeners with a new window into Japanese-American incarceration during World War II.

Their lyrics often weave together juxtaposing stories or primary sources to highlight the tensions between moments of humanity and inhumanity. In their song, “Instructions to All Persons,” they incorporate the title of General John Dewitt’s order to evacuate Japanese Americans with a softer, personal story about a young Japanese girl climbing to the top of the tower at the Santa Anita Racetrack—where Japanese Americans were detained before Manzanar. They hope this encourages students to better understand this period as a vital part of American history and see music as an entry point for students from all racial and ethnic backgrounds to unearth the complexity, universality, and humanity within a single person’s narrative.

So how can we use music to help students better understand the difficult histories of genocide? Consider some of these strategies for your classroom:

- Use Close Reading or Connect, Extend, Challenge strategies to analyze lyrics from songs that emerged from moments of genocide so students can consider how music can spark hope or commemorate a people and culture in its aftermath.

- Have students use primary source documents about mass violence to compose original songs or found poems.

- Use identity charts to explore the life and work of a musician like Komitas Vardapet, a prolific Armenian composer and ethnomusicologist who was arrested and suffered severe psychological trauma during and after the Armenian Genocide.

Learning about mass violence can often be a traumatizing or desensitizing experience for students. But just as performing “Eli, Eli” as a child opened my eyes to Hannah Senesh’s harrowing story, so too can music inspire students today to connect with those who lived through genocide and mass violence with heightened intellectual and emotional maturity.

Get started on exploring music and genocide with our featured collection, “Music, Memory, and Resistance During the Holocaust.” With three distinct lessons, students will draw on personal experiences with music to reflect on its ability to provide inspiration, comfort, and fight against injustice and then consider how music was used during the Holocaust.

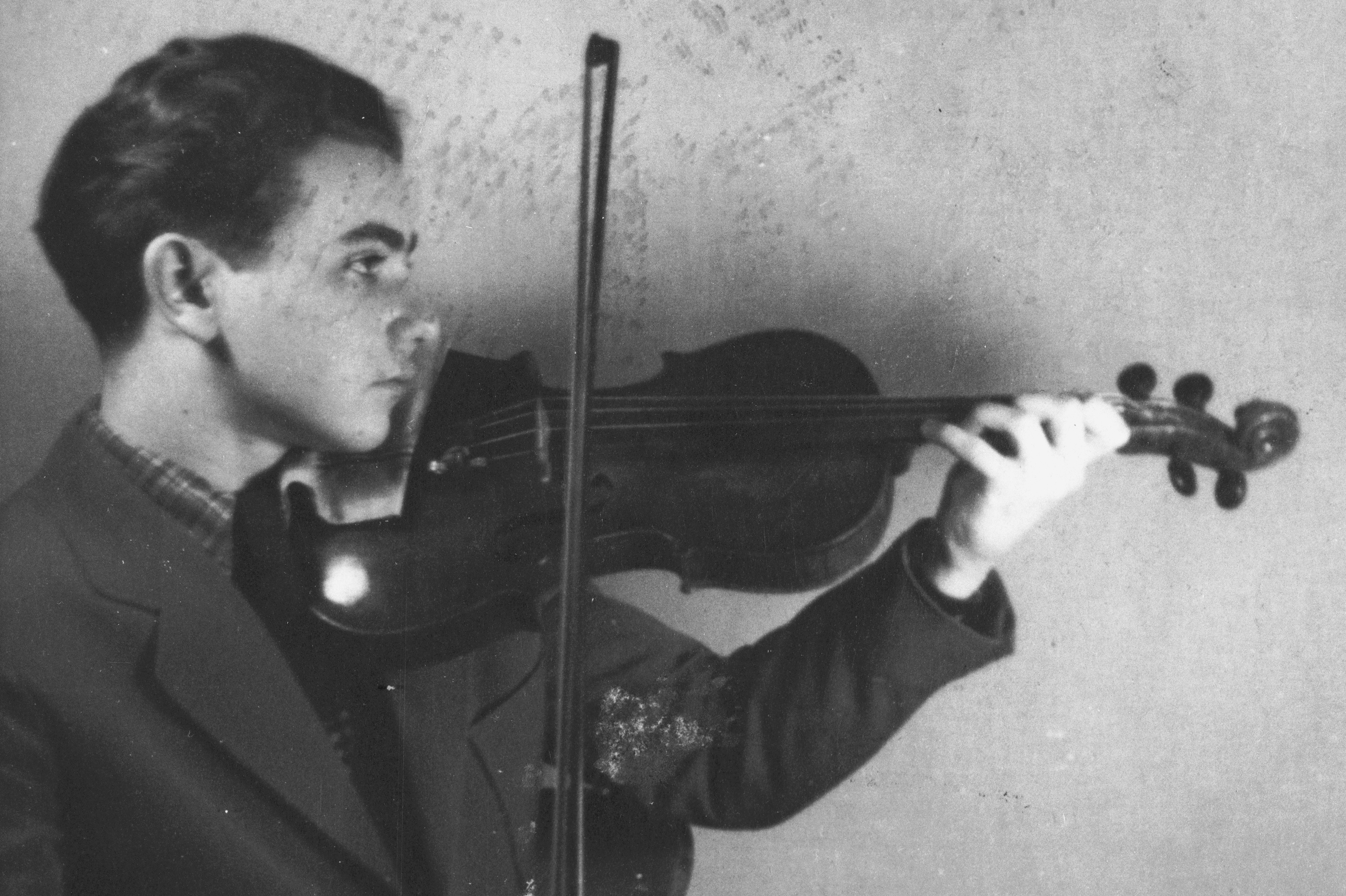

Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Dziunia Eichenholz Goop