Sonari Glinton is a journalist who read Night as a young boy and went on to study with Elie Wiesel when he was a student at Boston University. In a 2016 essay written right after Wiesel's death, Glinton describes how he was first drawn to Night simply because it looked like a quick read for a book report he’d been assigned to write. He was surprised to discover that he identified with its protagonist, even though, as a black boy growing up in Chicago, he and Eliezer would seem to have little in common. Still, Glinton saw himself in Eliezer’s love of books and theology and his status as part of an out-group in his society. Eliezer’s sense of fragility and vulnerability felt familiar.

Years later, while at Boston University, Glinton was selected to be a student in one of Elie Wiesel’s courses on literature and memory. Each student had to present a book to the class, and Glinton chose The Bluest Eye, a novel by Toni Morrison that so resonated with his own experiences as a black man that he broke down in tears during the class discussion. Later, he apologized to Wiesel and vowed to “get past” his feelings about race:

I remember him leaning in and asking why I would want to forget.

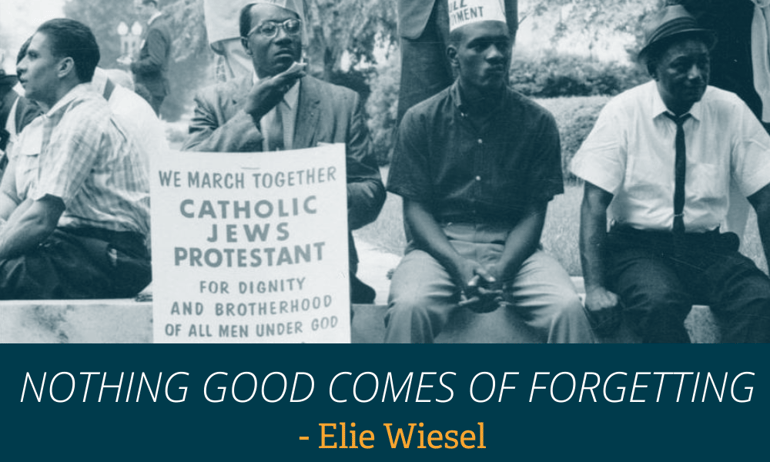

Memory, he said, wasn’t just for Holocaust survivors. The people who ask us to forget are not our friends. Memory not only honors those we lost but also gives us strength. In those office hours, he gave me a shield, practical words and thoughts that would help me—a gay, Nigerian, Catholic journalist. He gave me tools that would aid me in an often hostile world. Over the years, I have found myself quoting Professor Wiesel to white people who want me to “get over race.” “That’s old.” “It was a hundred years ago.” But Professor Wiesel had been emphatic: Nothing good comes of forgetting; remember, so that my past doesn’t become your future . . .

So, as a journalist, at times without noticing, I find myself helping others to remember or bear witness. I will not forget the victims of police torture I reported on in Chicago, or Lafonso Rollins, who was falsely imprisoned for rape . . . And when Trayvon Martin’s parents went to Capitol Hill and the press corps was less than sensitive, I remember kneeling in front of his grieving parents with my microphone. Why in those moments would I want to forget?

In my personal life, though, remembering—and making others remember—the unfairness of racism is a harder choice. I am NPR’s car reporter. For a normal gay man, being a car reporter and living near Beverly Hills should be a dream come true. I am a black man. That means that driving exotic cars or testing cars can be dangerous. I have been stopped at least five times this year . . .

During the 2012 presidential campaign, I was stopped in Michigan, Indiana, Iowa and Ohio. I have tried to shield my friends and co-workers from the fear, anger and indignities I face on a daily basis. That futile exercise has cost me dearly. I realize that I have a responsibility to let people know about what affects me. But I also know that, as a black man, that has costs as well. Mentioning race to white Americans has almost never failed to cause me pain or to be attacked . . . As I grow older, and feel the need to speak up more, I understand just a little the burden Elie Wiesel took on.

And that’s what I mourn when I think about him now. I mourn the man who taught me that in many ways laughter is the greatest victory. I mourn the man who saw me struggling and tried to give me tools to survive. I mourn the man who let me know that those who demand that I forget are not my friends. I mourn the teacher who made a solemn vow to me as a student in the ’90s and kept it. I mourn the fact that with him gone, I’m now more responsible for bearing witness. It saddens me that there’s still so much to bear witness to.

Want more insightful readings like this that can help your students explore the legacy of the Holocaust, the importance of memory, and the power of being a witness through Elie Wiesel's poignant memoir? You'll find this excerpt and more in our newly revised study guide, Teaching Night. This guide offers classroom-ready activities and a rich collection of media that takes students on an exploration of Wiesel's experience of the Holocaust and how identity is shaped and reshaped by the circumstances we encounter.