Before the US presidential election, Eric Liu wrote in a recent article in the Atlantic, “Whatever the outcome on Election Day, more than 40 percent of American voters will feel despondent, disgusted, and betrayed.” As we face this reality together, we have a chance to learn from the pivotal dilemmas and choices of our nation’s past as we pick up the pieces from the exhausting 2016 election cycle. We can look to the aftermath of the Civil War—another period of deep division within the US—to better understand how we got to this current divisive moment filled with vitriolic rhetoric.

The Reconstruction era (1865-1877) reveals the cyclical nature of progress and backlash and the fragility of our democracy while pushing us to continue to ask the question: Who is an American and who is America for? It attempted to find justice and reconciliation in the wake of unprecedented violence and destruction. It is one of the most significant crossroads and moments of possibility in American history.

Until recently, many scholars and popular culture viewed the era as a tragic low point of corruption and failure for American democracy. A narrative of the era, often called the "Lost Cause Myth" told a story of vindictive Radical Republicans, large-scale corruption in Southern state governments, and of how blacks were proven incapable of participating in democracy. That story ends with the “redemption” of the Southern States by valiant heroes who restored white supremacy.

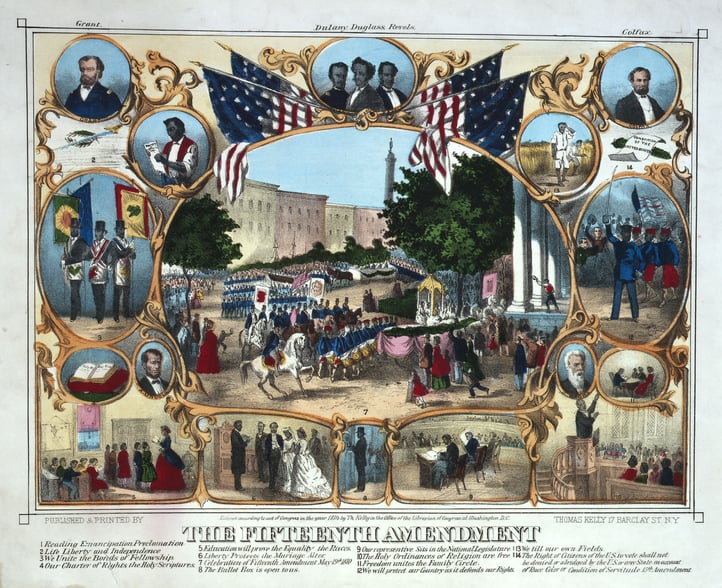

But that myth crumbles when students look at even some of the era’s accomplishments. During Reconstruction, the notion of equality under law and protections for the basic rights of the formerly enslaved were written into laws and the Constitution for the first time in US history. This included the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments as well as the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1875. If only for a brief time, interracial democracies existed in the defeated Confederacy. It was a momentous expansion of civil and political rights in the United States, followed by an enormous increase in civic participation and social change.

Millions of freed people, as well as thousands of black Americans in the North, were no longer prohibited from voting in the United States, and they were eager for their voices to be heard. Black Americans risked everything to participate in our democracy and struggle to determine their own future: from John Roy Lynch who was born into slavery and elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives in the elections of 1868 to the anonymous black farmer who spied on the Ku Klux Klan for the US Army in 1871. There was also the everyday struggles for equality black people engaged in everyday—from the black children who attended school for the first time to the black women who started businesses to attempt to determine their family’s economic future. This unparalleled nature of the expansion of political and civil rights in the United States under Radical Reconstruction had a tremendous impact on life in the South, where the majority of African Americans lived at the time.

But the economic, social, and political power that blacks began to accumulate was often met with waves of brutal violence and intimidation calculated to affect elections. If Reconstruction was a tragedy, it was because it failed to create true economic and political equality. Studying this time can lead to conversations about the corrosive effects of violence and intimidation on the ability of citizens to vote their consciences and speak their minds in a democracy. And it can shed essential light on the complex dilemmas we face today.

When we study history and make connections to the present, we cannot look for simple answers to our current dilemmas. We can ask our students to discuss what language is being used in national conversations about “us and them” and see how words can be used to dehumanize and exclude groups from a nation. We need to ask probing questions about our country and our choices. Why have our nation’s most difficult and violent moments occurred after progress in the struggle for black freedom, equality, and self-determination?

As President Obama’s second term ends, our country continues to struggle with the dilemmas of the Reconstruction Era. As Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative, said in his TED Talk:

“We have in this country this dynamic where we really don’t like to talk about our problems. We don’t like to talk about our history. And because of that, we really haven’t understood what it’s meant to do the things we’ve done historically. We’re constantly running into each other. We’re constantly creating tensions and conflicts. We have a hard time talking about race, and I believe it’s because we are unwilling to commit ourselves to a process of truth and reconciliation.”

At a time when we are once again caught up in heated debates about who is an American, voting rights, racial violence, and citizenship, we all need to find the courage to teach bravely to honestly face this history. The Reconstruction era has much to teach our students about the idea of democracy as a continuous process rather than a finished product. They can begin to understand why Reconstruction is referred to as “America’s unfinished revolution.”

Check out our lesson, "The Legacies of Reconstruction" to learn more about why the Reconstruction era is still so relevant to current events in America today. You can find this lesson and more in our full resource, The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy.

Photo Credit: By Thomas Kelly [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons