It can be so very difficult to discuss race with our children.

The conversation is particularly complex when it's about some of our nation's not-so-proud moments.Rather than face such moments head-on, sometimes we instead seek to protect our children (and even ourselves) from the pain and shame of the past, and so we often gloss over physical, emotional, and psychological suffering in history to get to a more palatable, less troubling version of those events. Moments like 1965 in Selma, Alabama, too quickly become "the victory of voting rights" rather than the painful history of a tired, yet determined, African American community that stood toe-to-toe against those who used terror, intimidation, and unjust laws to deny them opportunity to freely exercise the right to vote.

The pivotal moments in the new film Selma command that we ourselves slow down, sit with the pain, and then ask: Do we need to expose our children to this—the church bombings, mob beatings, and senseless murders depicted in the film? Do they need to see this history played out on the big screen when in their lives, they have only known a reality in which the Civil Rights Act has been law for decades? In other words, should we take our school-aged children to see Selma?

I chose to go watch it alone first, so that I could answer that question for myself as a parent of a 16-year-old African American girl. My daughter is more than aware of the violence of the Jim Crow South, but, like most teenagers, would rather not revisit it. I left the movie convinced that she needed to see it, but more convinced that I needed to see it with her.

I needed to see it through her eyes.

As the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church is bombed, I needed to be with my daughter to be reminded that in our family, we worship without terror.

As the marchers are brutally beaten on screen, her presence reminded me that she can protest without expecting to be attacked.

As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s family feared for his life daily, I needed to be reminded that my daughter fully expects daddy to come home safely each night.

As Dr. King laughs, eats, takes out the trash, struggles in his personal relationships, and even smokes, I hope she sees that our heroes are actually quite ordinary people. They are people who choose to do extra-ordinary things.

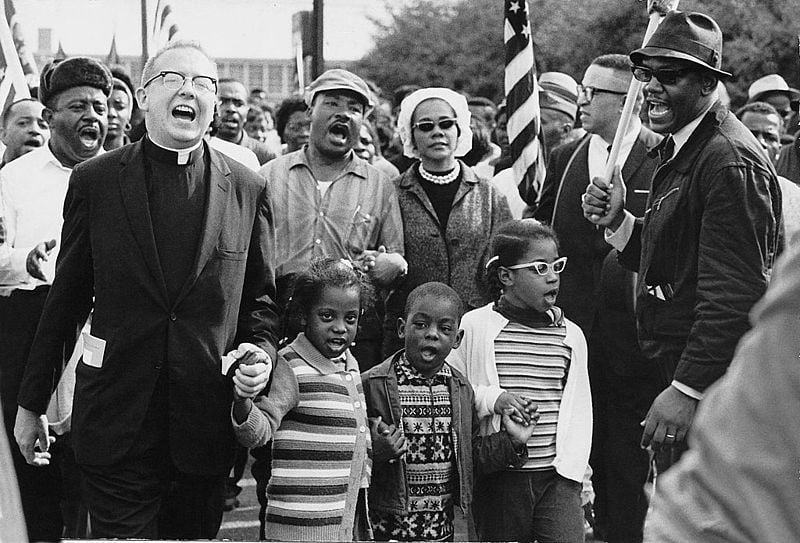

Dr. Ralph David Abernathy follows with Dr. and Mrs. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the Abernathy children march on the front line, leading the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. Photo courtesy of the Abernathy Family.

Dr. Ralph David Abernathy follows with Dr. and Mrs. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the Abernathy children march on the front line, leading the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. Photo courtesy of the Abernathy Family.I hope in watching this very real and raw film that my daughter sees the price that was paid for her peace of mind, and the responsibility that comes with that. Perhaps she will see herself and her peers as potential change agents.

Freedom remains fragile and tenuous today. It mirrors the fragility of democracy. The systemic injustice that denied Selma citizens the vote, the fear and hatred of the other, and the threat of violence can and does resurface as we continue to struggle toward a more perfect union. But our sons and daughters do live in a different world. Go see Selma with them. They will remind you of how far we have come. You will remind them of the price that was paid, and that there is so much more to be won.

Here are some guided questions that a parent or another adult can use to engage young people in a post-viewing discussion of Selma:

- The film is called Selma and not Dr. King. Why do you think filmmakers chose this name?

- Why would people risk their lives to stand up for the right to vote?

- What were the different strategies that those involved in the movement for voting rights debated?

- What were the different choices that people made throughout the time portrayed in the film that allowed for forward momentum in the movement for voting rights?

- What does this film add to your understanding of the civil rights movement? What would you like to know more about?

- Discuss a moment of courage in the movie that resonated with you.

- The March from Selma to Montgomery was a courageous demonstration. Can you think of other times in American history or today when groups of people came together to make change?

- What issue of unfairness in your community, country, or world do you think still need to be addressed.

- What is the most effective way to try to change these issues? What can you do among your friends, in your school, or in your community to help?

Suggested Activity:

There is a lot of public debate about whether the film gave proper credit to President Lyndon B. Johnson for his involvement in Selma and his eagerness to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965. A good family project could be to research Johnson's role and compare your findings to what the film suggested. For a greater historical understanding of the Selma marches, explore "Chapter 6: Bridge to Freedom" from the Facing History and Ourselves resource guide Eyes on the Prize. You will be asked to register on Facing History's website to view this free resource. Download now.

Further Resources:

Lynda Lowery turned 15 years old during the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. She was arrested 15 times over the years in which she participated in the civil rights movement. In this video, Lynda describes "Bloody Sunday" and the resolve that carried her through to the final march two weeks later. Watch now.

Find connection questions for educators and teaching resources in our blog post "Reconsidering Selma: Teaching the Stories Behind a Pivotal Moment in History."

Teaching Tolerance's Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a free classroom documentary that explores the Selma-to-Montgomery legacy through the activism of students and teachers. The accompanying viewer's guide encourages students in grades 6-12 to think about voting issues today and to consider what they would march for.